Contents

- Khan Tengri

- The Goal: An Independent 7000m Snow Leopard Summit

- Acclimatization Strategy: Pre-Acclimation, Expedition Enchainment

- Schedule and Calendar

- Khan Tengri Journal

- Images

- Thoughts on Khan Tengri

Khan Tengri

Khan Tengri is the high point of Kazakhstan, the second highest peak of the Tian Shan range, and one of the five 7000m snow leopard peaks. At 7010m Khan Tengri is also the world’s northernmost 7000m peak, although there is some contention as to whether its altitude should be considered 6995m on account of a significant ice cap adding to the peak’s geological elevation. Its northern latitude means that weather on Khan Tengri is unstable and often severe, and that climbers encounter a thinner atmosphere than is found at comparable elevations further south.

Khan Tengri is an exceptionally beautiful mountain on account of its prominence, its pyramidal shape, and its remarkable geological composition – the upper peak from ~6000m is a marble pyramid steep enough on its north face to remain mostly free of snow. Viewed from the north on a clear day, at sunset this pale yellow-gold marble catches the light of the setting sun and glows in a fiery, blood red hue. When viewed from the south Khan Tengri presents a perfect snow pyramid reminiscent of K2 in Pakistan or Alpamayo in Peru. The first time I experienced Khan Tengri’s sunset alpenglow I could only gape in awe – it is one of the most glorious, impressive peaks I have ever laid eyes upon.

The Goal: An Independent 7000m Snow Leopard Summit

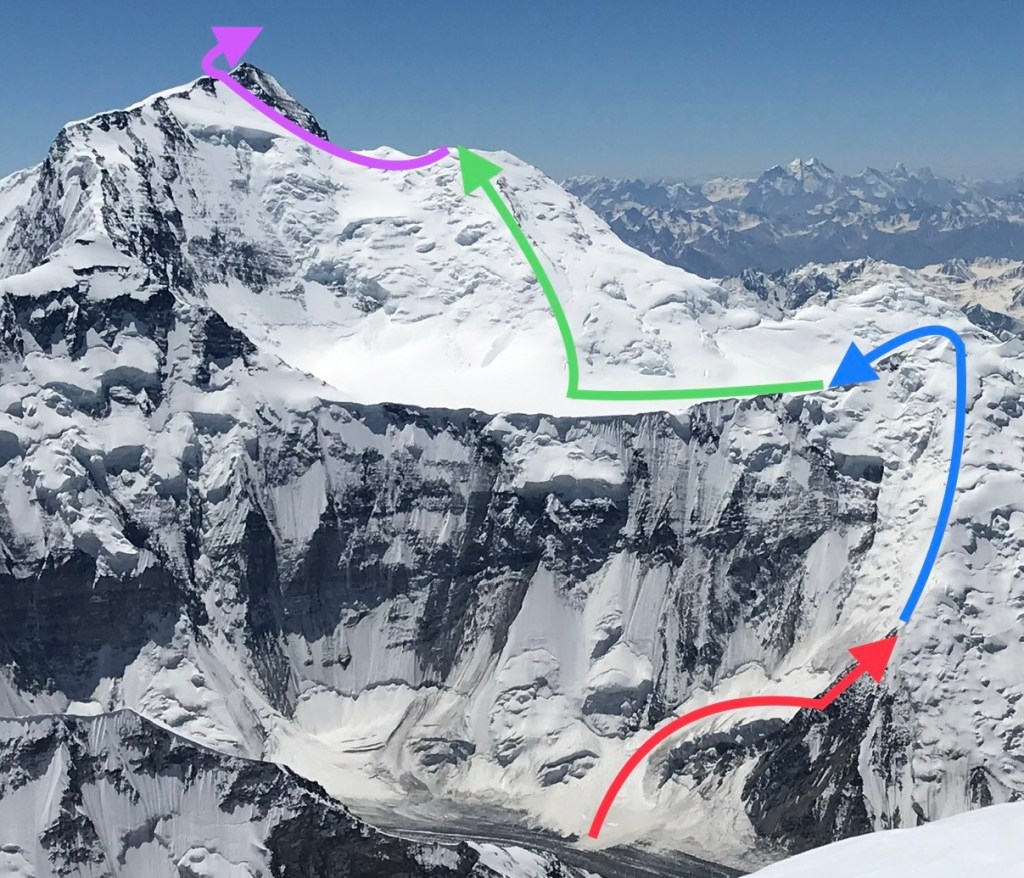

I had been keen to make an attempt on Khan Tengri for many years prior to my 2024 expedition. Khan Tengri is a mountain which, early on in my mountaineering progression, seemed utterly out of reach for me. I first laid eyes on images of the route in 2015 when Edgar Parra, a friend and mountain guide from Ecuador, had shown me photos from his ascent. For many years, Khan Tengri stood in my mind as a mountain which I thought I’d never be skilled or strong enough to climb, let alone independently (which I define here simply as ‘unguided’). With time and experience it began to seem more realistic, and possible for me to safely take a shot at. A variety of climbers I’d met over the years, including several friends, had recommended the northern route to me, emphasizing its viability for an independent or ‘solo’ (if such can be considered possible, given the fixed ropes) climb, its relatively good protection via seasonally maintained fixed lines, and its challenging, rewarding character. I had similarly been warned that the south route was unacceptably risky, due to significant serac and avalanche exposure.

After successful and highly rewarding experiences on Pik Kommunizma and Manaslu in the summer through autumn of 2023, I knew that I would be keen for another big mountain goal in 2024. While I shifted my focus entirely to rock climbing after Manaslu, and kept it there for the following six months, beginning in the early spring of 2024 I also committed time and energy to a training regime for mountaineering.

With no partners available on an aligned timeframe the expense, extreme physical toll, and guide support of a second 8000m expedition undertaken without friends did not seem particularly viable to me. At the same time, Pik Kommunizma had renewed my enthusiasm for the 7000m snow leopard peaks, and based on the advice of friends I felt confident that Khan Tengri could be doable if going alone. At this point I had summited three of the 7000m snow leopards, had climbed on those three peaks five times in total, and had done so independently – whether with friends or all alone – each time. I committed to an early start at the very beginning of the season, paid my deposit to Ak-Sai Travel, who now operate both the north and south basecamps on the Inylchek glacier, and prepared to return to Central Asia. I would warm up and pre-acclimatize on Pik Lenin, before shifting to Khan Tengri via the North Inylchek basecamp.

Acclimatization Strategy:

Pre-Acclimation, Expedition Enchainment

I pre-acclimated for Khan Tengri by making an attempt on 7134m Pik Lenin, the basecamp of which is also accessed from within Kyrgyzstan. I had previously summited Lenin in the summer of 2017, and in 2016 had also made an unsuccessful attempt; this was my third time on the mountain. I had a very rough time of things on Lenin on account of sustained inclement weather – enormous snow dumps and high winds – and never made it higher than ~6100m. Nonetheless, my time spent moving up and down Lenin, and resting at elevation, served as adequate acclimation for a rapid ascent of Khan Tengri. I summited Khan Tengri on my 7th day in North Inylchek. I did not feel as thoroughly acclimated as I wanted to be, largely due to my ‘low’ highpoint on Lenin, but my acclimation was definitely sufficient and served my goal wonderfully. Had I made it to the summit of Lenin during pre-acclimation, I believe that my subsequent time on Khan Tengri would have felt much easier than it did.

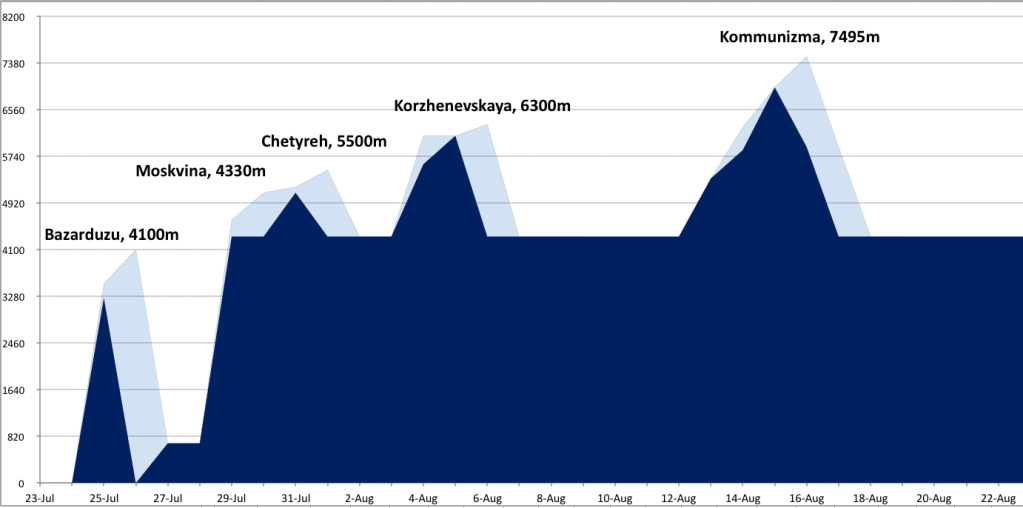

Pre-acclimation via expedition enchainment is a majorly effective strategy for tackling big mountains. It requires a significant time investment, which is a deterrent for many, but significantly improves odds of success and quality of experience (minimizing AMS and discomfort) at altitude. Climbing a ~7000m peak before a lower but technically demanding peak in the ~6000m range effectively mitigates altitude as a factor for the second climb. Climbing a 7500m peak and spending weeks in basecamp before an 8000m peak prepares the body with a thorough acclimation ‘foundation’, making a no-o2 ascent more realistic. At the time of writing I have successfully enchained four major expeditions above 7000m:

7134m Pik Lenin as preparation for an ‘overnight’ solo ascent of 5642m Mt. Elbrus, with no acclimation rotation on Elbrus.

7134m Pik Lenin leading into a rapid 5-day ascent of 5947m Alpamayo, where we skipped high camp and gained the summit on day 4.

7495m Pik Kommunizma as pre-acclimation for an ascent of 8163m Manaslu, where a single rotation to ~6650m was sufficient for my summiting without the use of supplementary oxygen.

7134m Pik Lenin prior to 7010m Khan Tengri, where I was able to summit on my 7th day without any rotations above ~4500m.

Pik Lenin is uniquely ideal for this purpose. It is inexpensive, quite high, highly accessible, very comfortable due to a developed basecamp, geographically close to me (I live in China), and relatively straightforward to rotate up and down on. When climbing Lenin it is notably easy to gain 5000m on nearby Pik Yuhin; this may be one of the most efficient and comfortable places to tag 5000m anywhere in the world. Lenin is a slog most of the way, but in spite of that I’d totally go back and spend time on Lenin (yet again!) in preparation for other peaks.

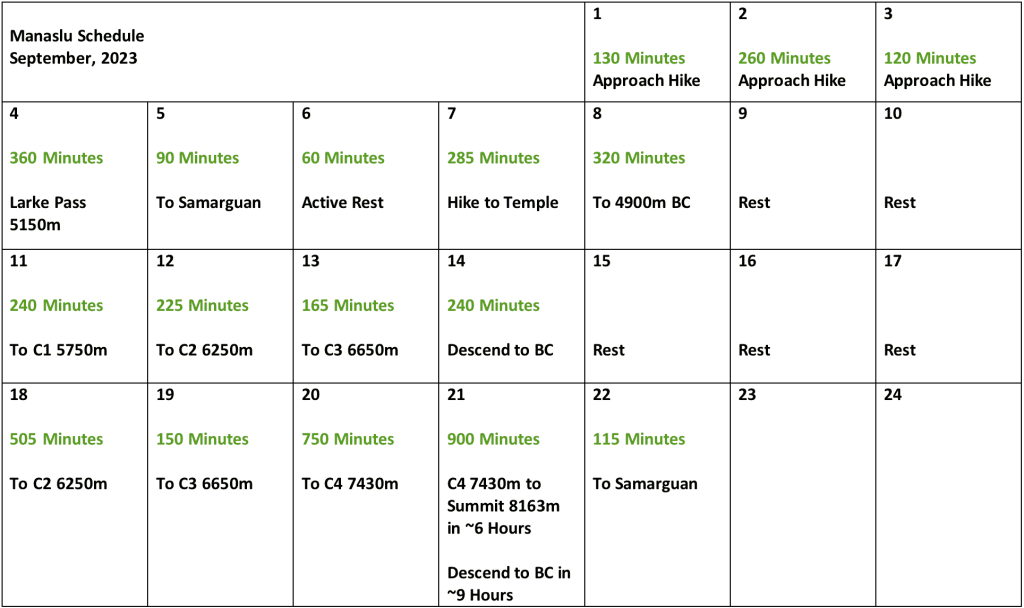

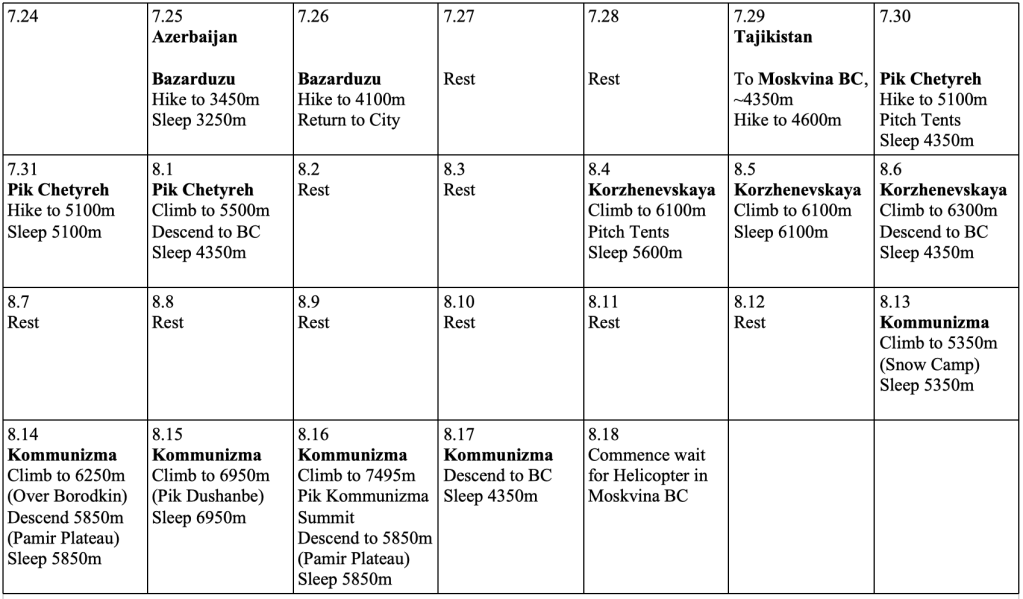

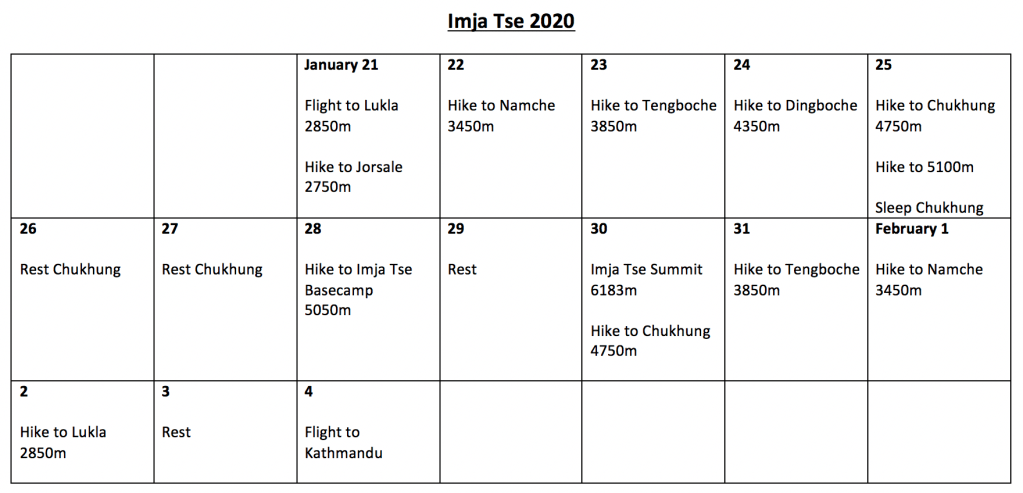

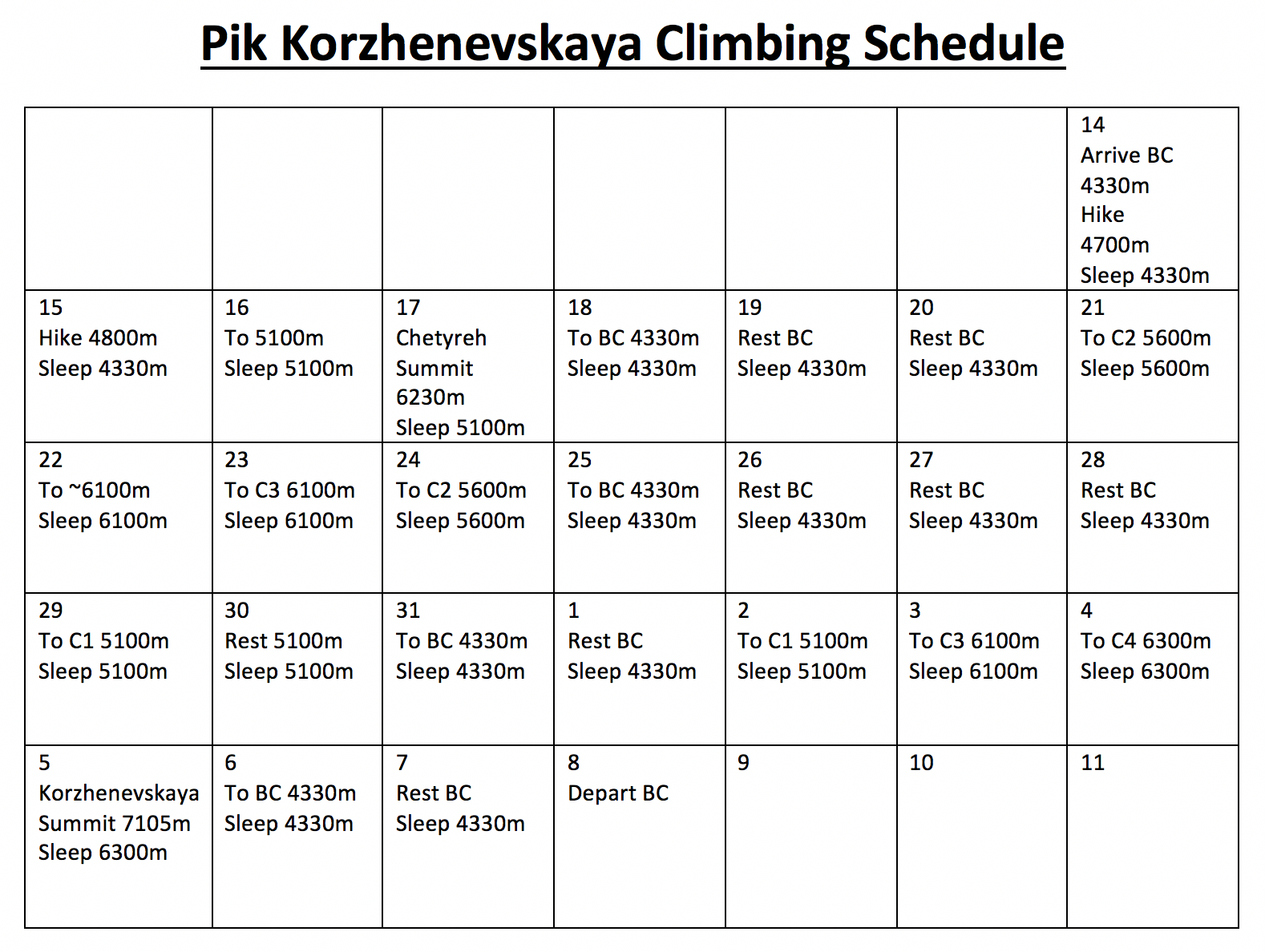

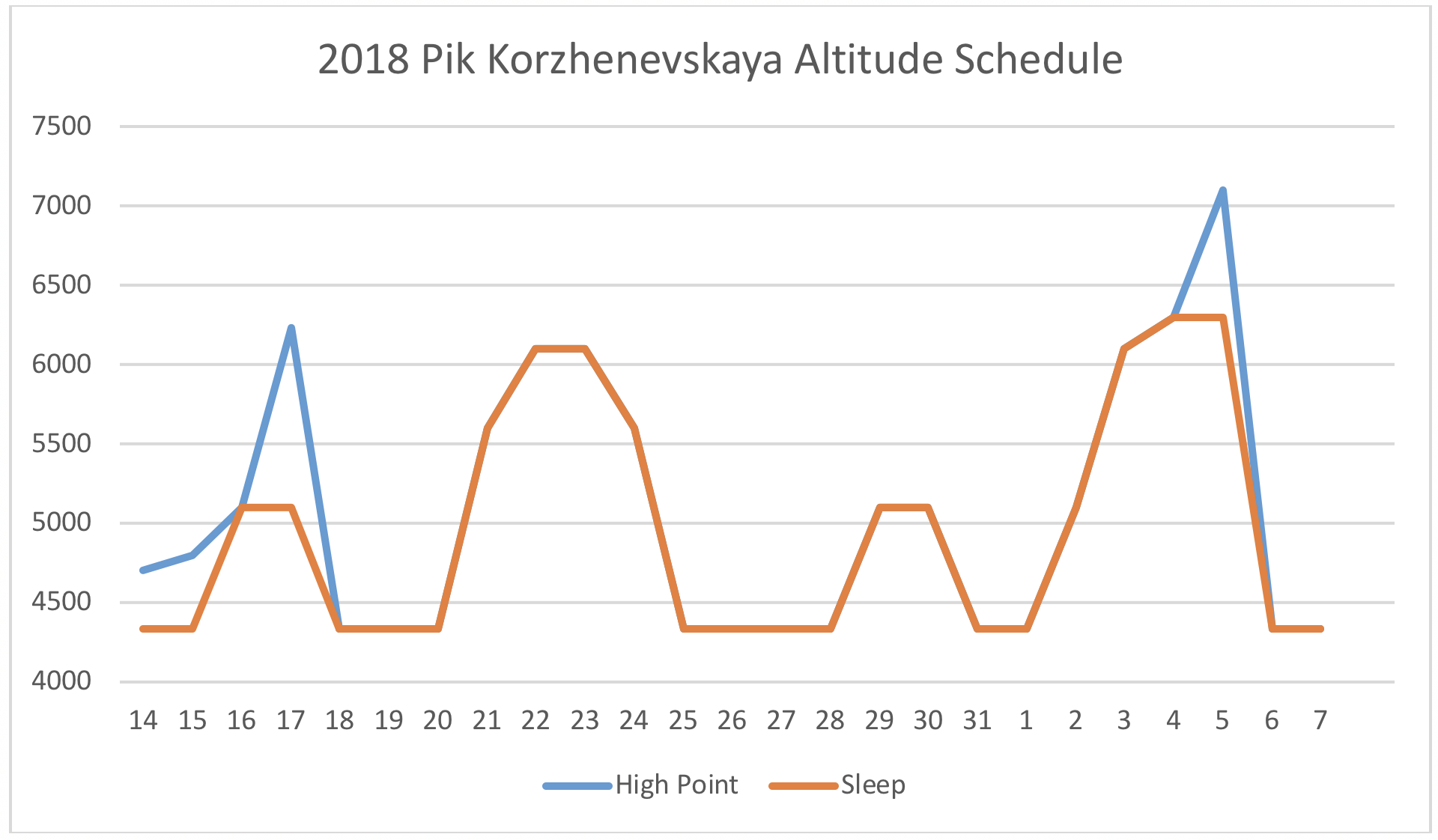

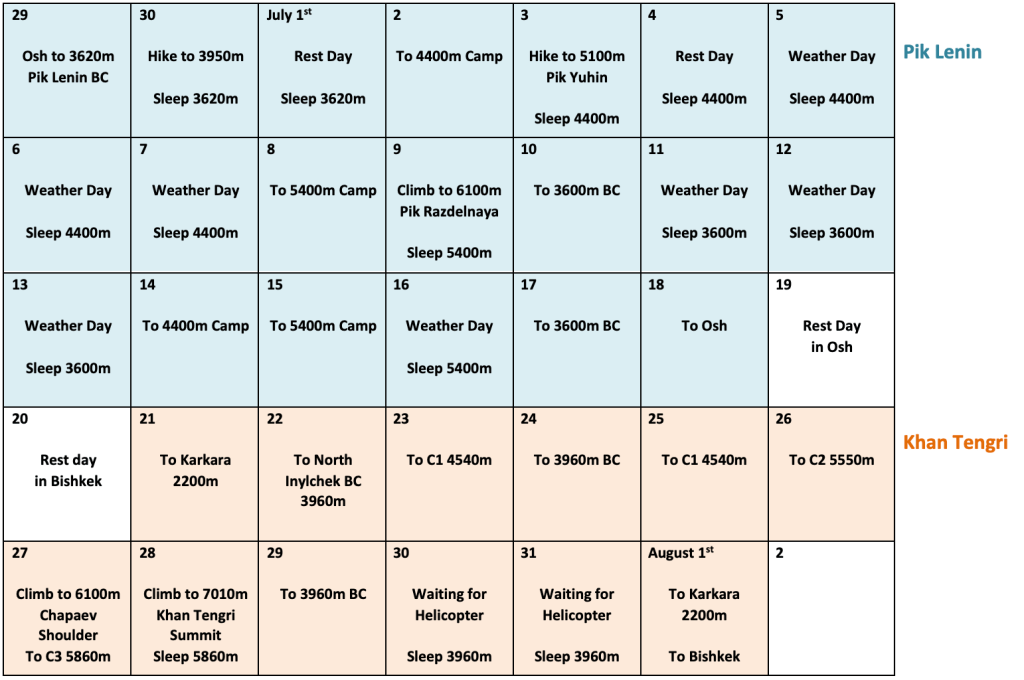

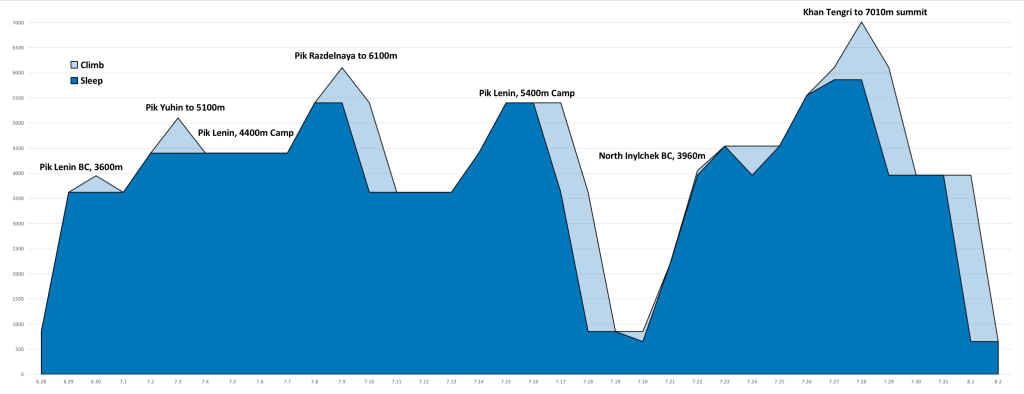

Schedule and Calendar

Here I have put together a calendar outlining my acclimation routine and climbing activity throughout my 2024 Pik Lenin and Khan Tengri climbs. I have likewise charted out the elevations used for acclimation rotations, culminating in an ascent.

Khan Tengri Journal

7.20

Arrive in 650m Bishkek.

7.21

Long, full-day drive to Karkara at 2200m. Many stops made the ride far lengthier than expected.

7.22

Helicopter ride for ~40 minutes through the valleys and into the mountains, to North Inylchek basecamp at 3960m, with first views of the Tian Shan range.

After lunch I went for a hike to crampon point at 4050m. Time of 45 minutes to get there, crossing moraine and dry glacier. A large river crossing was bridged with a wooden platform, which must be found via a specific ice valley. The river is fierce and powerful, quite dangerous, and must be crossed with caution.

North Inylchek Basecamp is small, rugged, spartan. Situated upon moving glacier, there are no permanent structures – indeed, the tents shift and slowly flow over time. My sleeping tent developed a distinctive slant and a troubling instability throughout my short stay in it. Food was consistently excellent, and Basecamp staff were friendly and professional. Yet, the camp feels cold and desolate when compared to Moskvina or to Lenin’s BC and ABC. There is no greenery, little life, much shadow and ice.

Khan Tengri presides above camp, majestic in its geometry. On clear evenings it glows orange and red at sunset, magnificent and ominous. Surrounding peaks are sharp and severe, numerous 5000m teeth rising alongside Khan Tengri, steep and pronounced. The Tian Shan are serious business, and very few of the visible mountains would be easily ascended. The proximity of the Inylchek glacier is startling; it is always underfoot, and its exposed ice lies a few short meters from camp. Climbers in camp visit it frequently for the washroom facility. Puddles of meltwater form, freeze, and drain throughout the day. Rivers of pure glacial water materialize at noon. The glacier is the highway which leads to the base of the route upward, and the foundation upon which camp is temporarily constructed.

7.23

2:20 pm depart BC.

3:35 pm arrive crampon point.

Time of 75 minutes.

6:30 pm arrive Camp 1, 4540m.

Time of 4:10 from BC.

I packed 6 days worth of supplies and all of my equipment for higher up. I had decided to go heavy and get the carrying over with in one shot – a strategy which has worked well for me in the past. I hoped to potentially even make my way into position for a summit attempt off of this heavy carry.

Soft snow made the heavy pack quite grueling to manage throughout steeper sections of the easy climb to Camp 1. I wished that I’d left earlier in the day; soft snow bridges were more than a bit dodgy. I used my jumar twice on fixed lines, making the slush easier to manage.

Camp 1 is small, but I had no problem finding a rock platform for my low-profile one-person tent. One benefit of a small tent is the ease of pitching in tight spaces!

7.24

9:20 am depart 4540m Camp 1

10:05 arrive Crampon Point.

11:05 arrive BC. Time of 1:45.

I woke up to steady, wet snowfall, and very poor visibility. I decided to bail rather than waste gas and food waiting around in Camp 1. Conditions were very damp. Ascending in such conditions would be miserable, and it would be hard to dry off properly once back in my tent.

I descended fairly quickly, although fresh snow slowed me down as I pulled ropes out and looked for the optimal path down. The moraine was lovely in the snow, and the flags which mark the way to the wooden bridge across the glacial river were much easier to see.

It was quite hot; I sweated inside of my water resistant layers and was thoroughly soaked once I got back to BC.

I was pleased to make a heavy carry to Camp 1, as I would never have to make that section of the route with a huge pack again. At the same time, I was disappointed not to get my equipment and supplies up to Camp 2, as doing so would have set me up nicely for a fast-paced summit attempt later.

7.25

Depart BC at 10:10 am.

Arrive Camp 1 at 13:10 pm. Time of 3:00.

After spending all of 7.24 in Basecamp, during sustained wet snowfall and poor conditions, the forecast shifted for the better. I agreed to move up on a similar time schedule as two other independent climbers, Lucas from Germany and James from the UK, and meet them in camp 2 on the 26th. We would then share a tent and stove in Camp 3 on the 27th.

I ascended in a light breeze and full sun, making a good pace whilst subjectively ‘taking it easy’. Conditions were much better than my first climb to Camp 1, as I left much earlier in the day. Having a lighter backpack was also quite enjoyable!

I observed two enormous serac collapses off of Khan Tengri’s shoulder, to the climber’s left of the north face. These did not threaten the route or its approach. It was very pleasant to arrive at Camp 1 with my tent pitched and food ready to eat. Conditions were flawless in camp, sunny and warm with a light breeze. I was easily able to dry my boots in the sun, and take a comfortable nap.

I ate well all afternoon and evening, and slept for over 9 hours. Light snow fell overnight, exactly as forecasted.

7.26

9:30 am depart Camp 1 4540m.

16:05 pm arrive Camp 2 5550m. Time of 6:35.

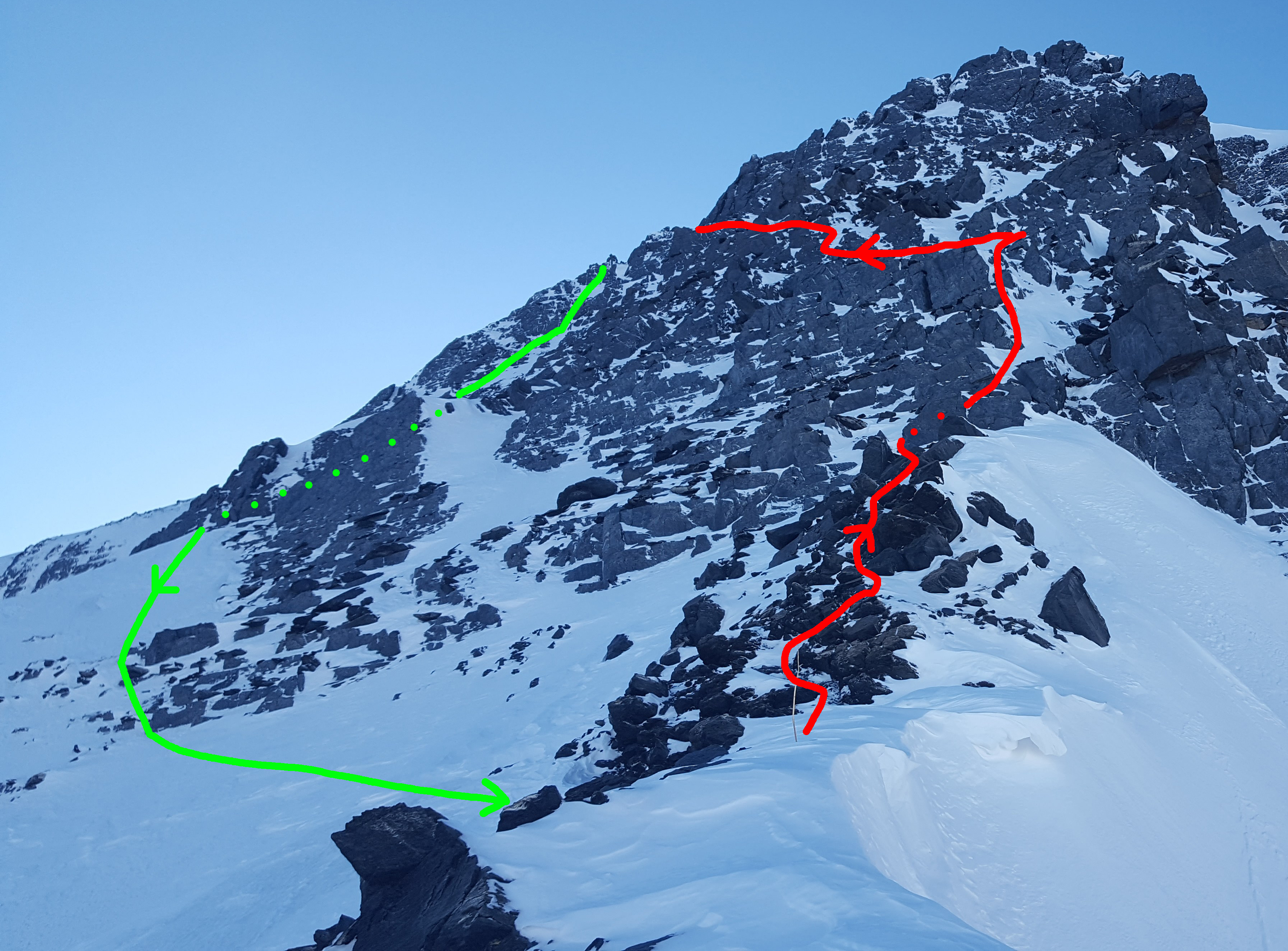

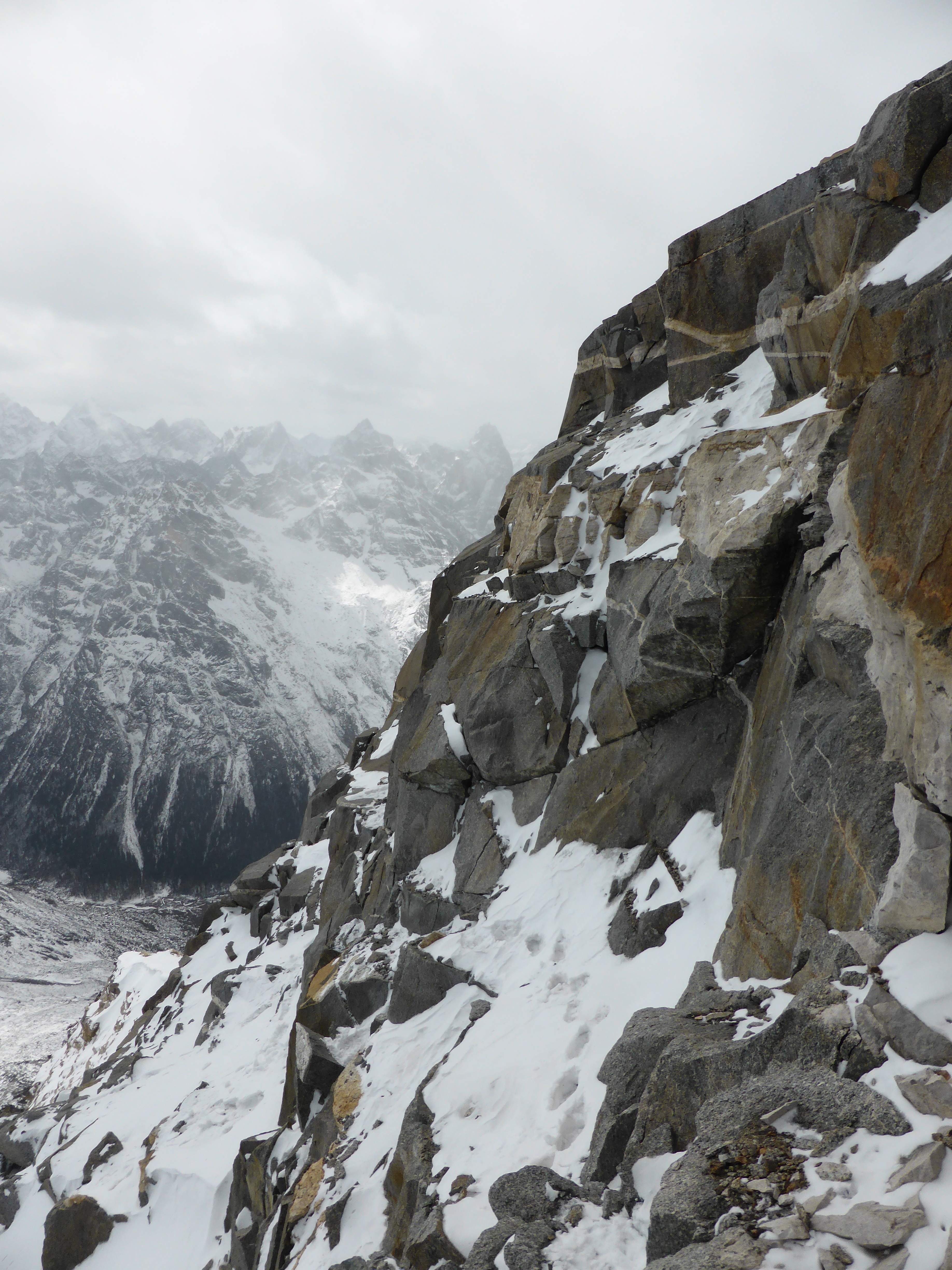

The route from Camp 1 to Camp 2 covers steep terrain, with several ice and rock steps. The rock steps and an exposed rock traverse were fun, and not strenuous for me, but the steep ice was brutal to front point while hauling my heavy backpack. I felt great with breathing and altitude, just absolutely slammed by the weight of my enormous pack. There were almost no places suitable for stopping to rest, due to the sustained steepness of the terrain. I had trained well for this expedition, but mostly via running rather than load hauling. This definitely contributed to my intense discomfort in managing my heavy pack while on steep terrain. Unfortunately, the remainder of the climb was like this; steep, and difficult with a big bag.

The weather was sunny and warm for most of the way, shifting into cloud and wind as I approached Camp 2. The entire route is fixed each season, and I kept my ascender on the lines for the majority of the climbing. With the ascender on, the route felt secure and reasonably well protected, but remains relentlessly steep. Without fixed ropes, the route between Camp 1 and Camp 2 would be an order of magnitude more strenuous, and I would not have felt at all comfortable soloing the vast majority of it. This would be a theme for the remainder of the route from Camp 2 to Camp 3 and then to the summit; if not already fixed this would be a very challenging and involved mixed route with what appeared to me to be fairly mediocre protection. Make no mistake, the majority of climbers – myself included – are only ascending Khan Tengri from the north due to the presence of the fixed lines.

Lucas and James met me at Camp 2 as planned. They arrived well before me, coming directly from Basecamp with light packs given that they had already deposited their tents, equipment, and supplies in Camp 2. I pitched my tent between theirs, and would leave my tent and some spare supplies here when the three of us moved up to Camp 3 together with a shared tent.

7.27

8:30 am depart Camp 2.

Arrive 6100m Chapaev Shoulder at 12:45.

13:25 pm arrive Camp 3 5860m. Time of 4:55.

More steep, sustained climbing from Camp 2 to Camp 3. Many rock and ice steps, but the fixed ropes made for secure climbing with the jumar on as a backup. The route up and over Chapaev shoulder is quite demoralizing, as it seems to go on forever – climbing still higher even while Camp 3 is clearly visible below! This aspect of the north route, paired with relentlessly sustained steepness, contributes to its (deserved) reputation for being difficult. Chapaev’s shoulder represents an additional ~250m of ascent and descent which must be covered – both on the way up and on the way down.

Views from the top of Chapaev shoulder were superb, and we spent fifteen minutes taking photos and looking at Khan Tengri’s west ridge under clear skies. The descent down to Camp 3 was very quick on firm snow. Camp 3 is a tiny snow ridge dropping off into large cornices to the north, and a steep face to the south, but we quickly found a flat space for our shared tent.

The forecast for 7.28 was promising, calling for 35 km/h wind with light snowfall in the morning and heavier snowfall in the evening. Lucas, James, and I decided to commit to a summit attempt.

7.28

Awake at 12:30 am.

2:45 am start.

12:20 pm Summit. Time of 9:35.

3:50 pm return to camp. Time of 13:05 round trip.

The route to the summit begins with a low-angled snow climb, but rapidly steepens. The majority of the route to the summit is relentlessly steep. There is almost nowhere to stop without anchoring off, and only a handful of small, level ledges. Two of these are sometimes used as high camps, and both were occupied by very tightly-pitched 2-person tents. James left our tent first, and Lucas struck out ahead of me. Lucas climbed impressively fast, and I wouldn’t see him again until ~100m below the summit. I caught up to James where the route steepened, and climbed more or less on pace with him until the couloir, where I moved on ahead of him.

The weather for our summit day was very much sub-optimal, with intermittent high winds and sustained snowfall throughout the ascent. Around 4 am I began to fear that the forecast was entirely incorrect, and that the projected evening snowfall had shifted forward to early morning. Beginning at around 8am there were two hours of vicious wind and driving snow wherein I seriously thought about bailing. I pushed through in the hopes of the weather shifting, and although high wind continued, the snow eased off.

I climbed in my down pants, down storm parka, and all of my base and mid layers. My base and mid layer system for the upper body was: 150g merino t-shirt, 150g merino long sleeve, 200g merino long sleeve, Patagonia R1, Patagonia Nanopuff. For my legs, my system was: 200g merino underwear, 150g merino leggings, 200g merino leggings (yes, two pairs of merino leggings, layered), Patagonia softshell guide pants. I use a Feathered Friends Volant storm parka, and Feathered Friends Volant down pants for 7000m peaks. I wear a single heavyweight merino sock. Gloves were an issue for me on summit day; due to constant manipulation of my jumar and personal anchor I was not able to wear my 8000m storm mitts during the climb. I wore a Polartec liner glove inside of the storm mitt mid-glove, a ‘crab claw’ with bifurcated index finger. If I were to return to Khan Tengri I’d purchase the warmest, heaviest five-finger glove I could find and leave my mittens behind.

Without my storm parka’s hood closure, a thick Polartec buff face mask and my goggles, my face would have become too cold to continue – I had to minimize any skin exposure to the air. I quite frankly would have majorly benefited from wearing my full down suit in the frigid, windy conditions we experienced – but carrying it up to Camp 3 in the nice weather lower down would have been miserable! Khan Tengri was a bloody cold climb; I had more gear than I thought I’d need, used all of it, was still cold, and am glad that I was especially cognizant of protecting my hands and feet while moving. The ‘wiggle step’ is an important technique to master; wiggling the toes and fingers in line with every single rhythmic rest-step higher.

Dawn eventually cracked the frozen night sky open, revealing Pik Pobeda in the distance. Pobeda’s summit glowed warmly, while its enormous massif spanned across the horizon below. A fearsome mountain, Pik Pobeda is the hardest and most dangerous of the snow leopards, the ‘gatekeeper’ to finishing the five. Sunrise did not, unfortunately, bring warmth. Khan Tengri’s normal summit route follows the west ridge, which does not catch morning sun, and the wind was too intense for daylight to make much of a difference.

At around ~6800m, I roughly approximate the elevation here, I reached the couloir where the ridge traverses north onto the mountain’s upper slopes. There was a significant bottleneck here, as the handful of climbers ahead of me worked their way past the sketchy pair of core-shot fixed ropes. Unanchored in the middle, the ropes protected the traverse from a deadly fall, but did not serve to keep a climber comfortably on route. They were very loose, difficult to jumar in a controlled manner, and majorly slowed down the people ahead of me. I reckon that I waited for almost 45 minutes for my shot at this short ~15m of the route; when it was my finally turn to climb I used my axe for balance and delicately cramponed across the traverse with the ropes held as taut as possible. On the way down, rappelling this section was also annoying, and one of the slowest sections to navigate.

Above the couloir I finally gained Khan Tengri’s upper slopes, and was greeted by the glory and life-bringing warmth of the sun. The sunshine revitalized me, filling me with hope and renewed motivation. Immediately overheated, I anchored myself to slather sunscreen onto my face and remove my down pants. Taking the pants off would prove to be a mistake, as I needed to put them on again when intense wind resumed less than an hour later. Above the couloir is a fun rock step on beautiful marble. Fresh fixed lines made for perfect protection here, and I racked my axe so that I could free climb. I made use of a hand jam, stemmed, and pulled some easy rock moves with my jumar as backup. This section of rock was by far the highlight of the route for me – class 5 climbing and a hand jam above 6800m!

The final slopes to the summit are moderately angled, but were arduous in their own way due to intense wind and cold. Snow quality was acceptably firm and the route up was easy, but weather made for significant discomfort. I met Lucas here, on his way down from the summit, and we exchanged words of encouragement. Near the summit are several large boulders, and enough small, flat areas for a few tents. Some ambitious teams do apparently camp up there, although the prospect of hauling gear up makes me shudder.

When I reached the top, I let out a shout of triumph. It had been a long push, in poor conditions, and I was delighted and relieved to have made it. Each meter was fought for and hard earned. The summit day was physically and mentally difficult. A lot of this can be attributed to the impact of weather conditions, especially wind. The summit plateau was excruciatingly cold, due to intense and sustained winds. I was only able to stay for a few minutes and hastily take photographs of Pik Pobeda, Khan Tengri’s summit cross, and the surrounding terrain. A friendly Ukrainian climber who was already on the summit when I arrived generously removed his gloves in order to take my photo for me. I climbed the final ~10m up the ice cap, to the true high point of the mountain, the controversial final meters which designate Khan Tengri as a 7000m peak. James arrived as I was headed down, and we quickly took a selfie together.

The descent to our high camp tent felt endless; rappel after rappel after rappel, mostly on iced and knotted fixed lines. I made a concerted effort to remain focused and intentional in my actions, double check my systems, lock my carabiners, and generally be as careful as possible. I was fatigued, mentally and physically, and knew that mistakes would come easily should I allow them.

Back at the tent, I clocked my round-trip time at 13:05, not very fast at all. I believe that inclement weather slowed me down significantly. I also lost between 30-60 minutes due to the small bottleneck at the couloir traverse fixed lines. I also could definitely have trained with better specificity; my calves persistently felt like an athletic bottleneck on Khan Tengri. I was not fully prepared for the amount of front-pointing and sustained steep terrain, and had been especially worn down by the struggle of managing my enormous backpack during the steep load carries.

7.29

10:55 am depart Camp 3.

1.5 hour rest in Camp 1.

18:00 pm arrive Crampon Point.

~3 hour rest at Crampon Point.

21:50 pm arrive BC.

James, Lucas and I slept in, and took our time eating breakfast, drinking coffee, and packing up. A massive avalanche woke Lucas and I in the early morning – it swept the southern route below Camp 3. A serac collapse off of Pik Chapaev had triggered the slide, a common occurrence given Chapaev’s topography above the southern route’s approach gulley. Lucas and I turned our radio on to listen for any distress calls from the south: nothing. On return to basecamp we would learn that one man had died in this avalanche, and that two others had been seriously injured.

The climb from Camp 3 back up Chapaev’s shoulder was slow and annoying – yet more jugging on the jumar. Happily this ~250m climb would be the final use of my ascender on the route.

Endless rappelling on the way down. Chapaev’s shoulder is around 6100m high, and the base of the route sits at roughly 4000m. Accounting for some sections of smoother terrain and short sections of walking, I figure that I easily rappelled 1800m in total. Many fixed ropes were icy, pulled too tight by snowfall or glacial shift, or were knotted in awkward places mid-rap. Diagonal rappels and raps on loose scree or deep snow began to add their toll both physically and mentally.

In Camp 1 we stopped to pack our tents and spare supplies, and take a much needed break from rappelling. We stopped again for several hours to regroup as a trio at Crampon Point, drying our boots and socks in the sun and gazing at Khan Tengri’s splendor.

We were all exhausted, and the final easy dry glacier crossing to basecamp felt like a bit of a death march. On return to basecamp – manna from heaven! A hot meal, a cold Coca Cola, and the Sauna facility were all ready and waiting for us! Never before have I slept so well after drinking a full liter of cola.

7.30

Rest day in Basecamp. I felt quite alright this day, not particularly worn down, albeit with a very healthy appetite. The weather began to deteriorate, and we were grateful that we had summited when we did.

7.31

Helicopter scheduled for today, but cancelled due to foul weather. High wind and steady rain all day long.

8.1

Helicopter at 11 am back to Karkara camp. Long drive back to Bishkek, total time of ~6.5 hours with minimal gas station stops.

Images

Thoughts on Khan Tengri

Khan Tengri via North Inylchek was a difficult climb. The terrain and demands of the ascent, even with fixed lines in place, represent a totally different scope of ascent than Pik Lenin or Pik Korzhenevskaya, the other two ‘lower’ 7000m snow leopard peaks. Weather was challenging, and extremely cold on summit day. Load carries on relentlessly steep terrain posed a real challenge, and are something which I will endeavor to train for with better specificity in the future. I was delighted to summit Khan Tengri in an independent style, and in good time due to pre-acclimation. Pik Lenin had been a total wash, a boring grind of a climb with days upon days spent waiting out foul weather, and having that ascent pay off with success on Khan Tengri was a joy. North Inylchek is a spartan base camp, but food was both sufficient and good, the sauna was delightful, and the staff were highly capable. Ak Sai runs a solid operation, and I have been very impressed by their basecamps on Moskvina, Pik Lenin, and the Inylchek glacier. Ak Sai’s pricing is of quite good value, in my opinion, if just paying for basecamp.

Khan Tengri is one of the most beautiful mountains I have ever climbed, or even seen! This is a special peak, one of the world’s most remarkable, unique in its character. The marble cap of the upper mountain is unlike anything I have ever seen elsewhere – I’d love to hear a geologist go into greater depth as to its formation and nature. Witnessing the blood red glow of Khan Tengri at sunset is indelible, a powerful mountain experience which will never leave me.

Editing this journal as I am, in late September of 2024, it is interesting to compare my physical state after Khan Tengri, with that of my condition after Manaslu – Khan Tengri was subjectively a ‘harder’ climb than Manaslu, yet Manaslu was much ‘harder’ on my body and mind. After Khan Tengri I felt pretty good, had an appetite and energy, had lost about 4kg of body mass, was able to rapidly begin regaining lost weight. After Manaslu I was physically ruined, suffered from short term cognitive fatigue or impairment, had no appetite for about a full day, and had lost about 7kg of body mass. My rock climbing performance took roughly three months, around 12 weeks, to fully recover from Manaslu. As I write, I subjectively feel that my rock climbing performance has taken only about 6-7 weeks to recover from Khan Tengri.

I am of the firm belief that the southern route to Khan Tengri’s west ridge (the northern and southern routes share the same summit ridge) is unacceptably hazardous, exposed to severe and unavoidable objective risk in the form of serac-induced avalanche off of Pik Chapaev. We saw or heard numerous slides on the southern side of the route, and multiple fatalities and grievous injuries occurred in 2024. I am compelled to put this to writing, phrased in strong language: If planning to climb Khan Tengri, you should prepare for and train for the northern route. Do not play dice with your life on the southern side of the mountain.