Contents

- The Goal: 8000m Without Supplementary o2

- Acclimatization Strategy: Expedition Enchainment

- Day-by-Day Climbing Schedule and Route

- Thoughts on Manaslu

I climbed to the true summit and absolute highpoint of 8163m Manaslu on September 21st, 2023 with a commercial expedition organized by Imagine Nepal, and 1:1 guided by Pasang Dawa ‘Pa Dawa’ Sherpa. I did not use supplemental oxygen at any time during my ascent or descent.

This is a written trip report for my climb. For photographs, take a look at this post.

The Goal:

8000m Without Supplementary o2

An 8000m summit without the use of supplementary oxygen had been a major personal goal of mine for a long time. The economic expense, training rigor, time commitment, and uncertainty surrounding my ability to physically handle 8000m had deterred me from making any attempt pre-Covid, with the rationale that I could continue to build more 7000m experience first. Uncertainty, especially, was in hindsight a major factor for me; how would I handle the elevation without o2, and how could I know or fully prepare without just committing? The high-friction environment created by Covid policies in China, where I live, suddenly put a hard stop to any possibility of my getting onto an 8000er, or even mountaineering at all, for three and a half years. Near the end of Covid I arranged to take a one year sabbatical from work, thus satisfying the time commitment involved, and commenced a structured training regime.

With no stable partners keen to make early plans, and absolutely not confident in targeting my first 8000er alone, I resolved to accept the cost of climbing guided with a commercial operator. Manaslu, whilst still very expensive, was the cheapest 8000m peak one could climb guided, and its normal route was very straightforward for me to research and get a sense of – especially so given excellent content published by Explorersweb. I chose to climb with Imagine Nepal for a number of reasons. Imagine Nepal stood out to me as a local Nepali operator, as the operator responsible for rope fixing, and due to their solid track record in climbing to Manaslu’s elusive true summit – and not a ‘false’ foresummit – during the two seasons prior to my attempt. The choice worked out for me, and Imagine Nepal was as fine an operator as any on the mountain; basecamp provided excellent rest and recovery, Pa Dawa was an absolute unit of a guide and partner, and all logistics and transfers were smooth and professional.

Acclimatization Strategy:

Expedition Enchainment

Enchaining expeditions, climbing multiple high elevation peaks in a row with the goal of robust long-term acclimatization, is a tactic which I have made productive use of several times. In the past I have enchained Pik Lenin with Mount Elbrus, and Pik Lenin with Alpamayo, for excellent outcomes. The primary difference between a lengthy singular expedition within one region, and a link up for acclimation carry-over, is in the loss of exposure to elevation midway due to travel and transitions. I am not aware of any well-established science to the persistence of acclimatization, nor its rate of degradation once removed from a hypoxic environment. However, I know from prior experience that I am fine for roughly a week at sea level without any significant loss of acclimation, and I also believe that – if smoothly executed – transitions at low elevation can function as good recovery intervals for the body.

Prior to Manaslu I undertook a significant expedition to the Pamir in Tajikistan, where I successfully ascended 7495m Pik Kommunizma, another long-term goal of mine. This climb, unguided and with friends, was deeply significant for my subsequent success on Manaslu. I had plenty of time in Tajikistan to refresh myself on my mountaineering systems and habits, get back into the rhythm and challenge of high altitude climbing, and most importantly was able to rigorously acclimate before setting foot in Nepal. Thorough acclimation was absolutely critical to ascending Manaslu without bottled oxygen, and I am certain that without Pik Kommunizma, plus significant time resting in Tajikistan’s 4330m Moskvina basecamp after that ascent, I would have needed at least one additional acclimatization rotation on Manaslu. The schedule followed by climbers making use of bottled oxygen is absolutely not suitable for a no-o2 ascent, as it involves a quite limited scope of acclimation.

I had spent an unpleasant night at 6950m camp on Kommunizma before ascending to 7495m, which provided serious stimulus for my body to adapt for even higher. The risk I faced was in losing this deep acclimation by spending too much time at sea level; I thus opted to remain in Moskvina Glades Basecamp for over a week after Kommunizma, and tried to get back to altitude as quickly as was possible upon reaching Nepal. As part of this strategy, I opted to save money by trekking into Manaslu basecamp, clearing 5150m Larke Pass and spending several additional nights above 4000m. The approach trek had me back to elevation much faster than a helicopter would have (helicopters fly in somewhat last minute, only when basecamp is fully constructed), and I also felt that the trek served to reinforce my base acclimation from living at 4330m Moskvina Glades. Nutrition and rest during most (I’ve heard horror stories about the Makalu approach!) approach treks in Nepal are a non-issue, due to well established tea house infrastructure, and an approach trek on a popular route (as in the Khumbu region) serves as a very low intensity acclimation interval. I felt quite strong from the get-go on Manaslu, with no issue sleeping at 6650m C3 on my first and only rotation, and no issue sleeping or eating at 7430m C4 during my summit push. The ability to rest and eat properly at these elevations set me up with a superb foundation of energy and motivation for my summit attempt.

My complete acclimation schedule, including Manaslu’s summit, is visualized below. Dark blue shows sleeping elevation, and light blue indicates the daily high point:

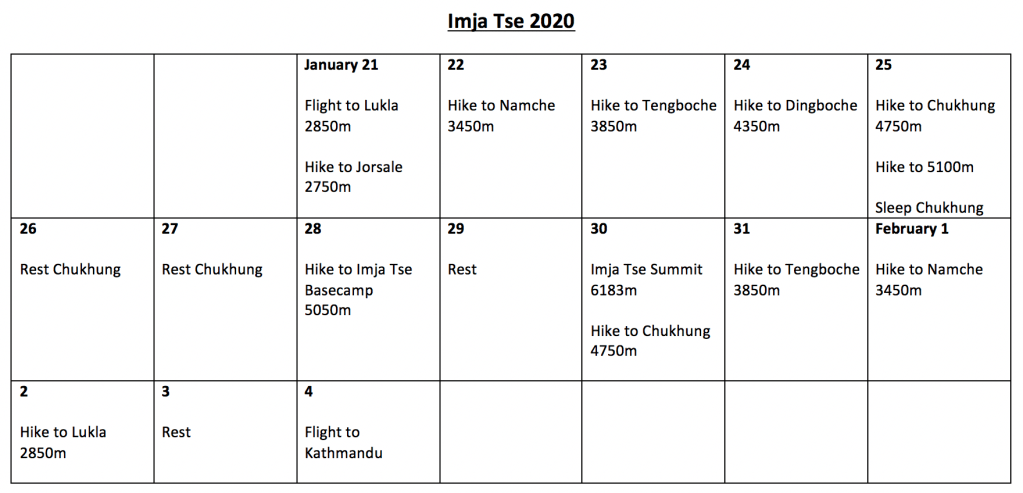

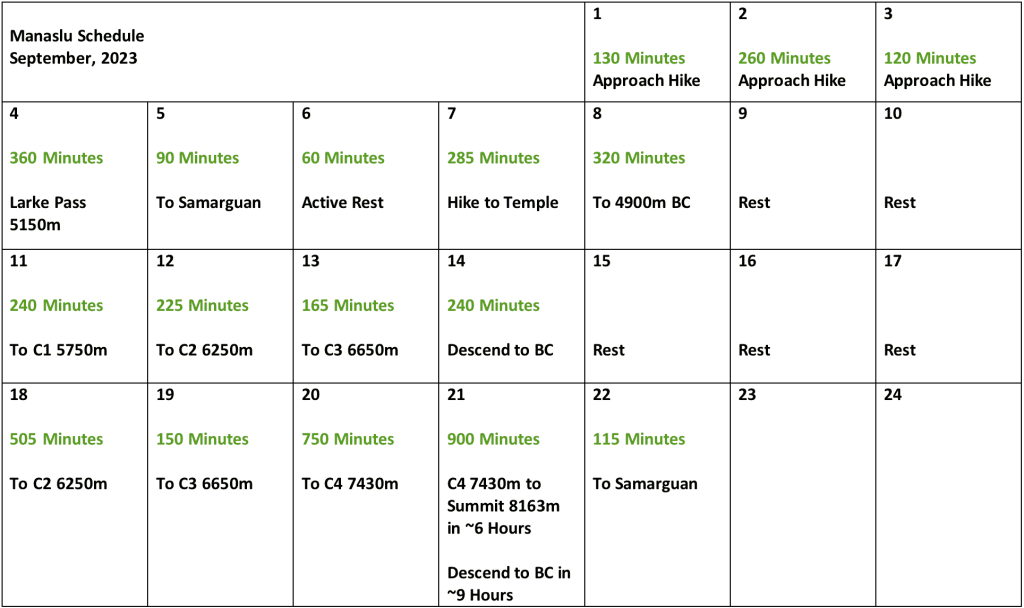

Day-by-Day Climbing Schedule and Route

Here is a calendar outlining my schedule throughout the approach hike and climb. I tracked output as minutes spent moving, whether ascending or descending.

September 1st – 5th

Approach trek.

The approach began with a long drive split over two days, from Kathmandu to the trailhead for the Manaslu circuit trek. I saved a significant amount of money by undertaking the 5 day approach trek instead of helicoptering into basecamp. This also served to reinforce acclimation nicely; on September 4th I cleared 5150m Larke Pass, and I spent two nights sleeping above 4000m during the approach.

Weather was quite unstable and rather poor throughout the approach. There was intermittent rain, high humidity, and one full day of torrential rain where we decided to hunker down in a tea house and just wait. The approach trek was otherwise pleasant enough, with very well broken trails and comfortable tea houses the entire way. The approach hike ended in Samarguan, a small village with guesthouses catering to both hikers and climbers.

A donkey train took my equipment separately, and Pa Dawa and I only carried day packs throughout the approach hike. The donkey with my bags was delayed, and my equipment made it to Samarguan just the day before we hiked up to basecamp! Luckily I had packed a thorough day bag, with everything that I needed (except an umbrella!).

The terrain throughout the approach hike was lovely higher up, especially the mountains surrounding Larke Pass and the high alpine lakes outside of Samarguan. In nice weather the Manaslu circuit would be a worthwhile hike unto itself, although the nearby peaks are less stunningly pronounced than those in the Khumbu region. Unfortunately, Manaslu did not reveal itself to me throughout the approach hike, and remained wreathed in clouds on days where I would have had good views in clear weather. I would not set eyes upon the mountain’s profile until the day of my first rotation to elevation.

September 6th – 8th

Active rest days in Samarguan, followed by a move to 4900m Basecamp.

I went for an afternoon hike up to an alpine lake on one day, and a much longer hike up to a high temple on another. The hike up to 4900m basecamp was slow but easy, on a well beaten trail. The route to basecamp was crowded with porters, hauling equipment up both for climbers and for basecamp infrastructure. We stopped for local milk tea halfway up, and took our time hiking at a relaxed pace. The weather was truly atrocious, rainy and very wet, and gave me cause for concern as to the conditions we would face higher on the mountain.

Manaslu is a very wet mountain, apparently due to the topography of the nearby valleys. On arrival basecamp was wreathed with mist and fog, there was incessant drizzle, and an umbrella became a truly critical piece of equipment. If attempting Manaslu, bring an umbrella for use on the lower mountain! We immediately went to the meal tent of our basecamp, where hot drinks and a space heater insulated us from the wet. My personal tent was spacious, and with double walls was insulated from condensation.

In reflection, the mood was somewhat grim those first days in basecamp, with very wet weather and heavy precipitation casting a shadow over our perceived chances for a smooth climb on the upper mountain. Moving between rest tents and meal tents was tenuous, exposure to the rain and cold making it difficult to stay dry and comfortable. The initially foul weather did eventually stabilize into one of the best seasons Manaslu has ever seen, with an enormous multi-week weather window of low winds and zero precipitation.

September 9th – 10th

Rest days in 4900m Basecamp.

I got to know the other climbers climbing with Imagine Nepal, meet more of the local support staff, and get a sense of the basecamp environment. I made daily forays higher, up to ‘crampon point’ at the edge of the glacier, in an effort to push my acclimation a little bit. Satellite internet service was available, and I was able to keep in touch with family and friends.

Weather was awful, constant drizzle and high humidity. It was difficult to stay dry, even inside the vestibule of my tent. I found myself wearing my down pants every day in basecamp, to deal with the penetrating humid cold.

September 11th

4900m Basecamp to 5750m Camp 1.

Manaslu revealed itself to me for the first time today, as the clouds parted and the mountain appeared from the mist. A rainbow appeared in the humidity over the peak, crowning the pinnacle – a false foresummit summit visible from basecamp – with colour.

My first day on the upper mountain, gaining the glacier and Camp 1 at 5750m. The lower icefall above basecamp is broken and heavily crevassed, and the route to Camp 1 was winding and somewhat indirect. The climbing was extremely easy, on very gentle slopes throughout, just with quite a bit of crevasse navigation via fixed ropes. There were numerous sections which would have been incredibly dangerous to cross without the fixed lines in place.

September 12th

5750m Camp 1 to 6250m Camp 2.

This section presented the ‘lower crux’ of the route, with a complex icefall navigation and several steep ice steps to ascend. The entire route was fixed, so the 80 degree to overhanging ice cliffs within the icefall required only easy jumaring. Regardless, each ice step was crowded with climbers, and they presented bottlenecks to movement. Porters carrying oxygen and heavy loads of equipment to the upper camps had to ascend slowly, and some climbers appeared very uncomfortable managing the steep terrain.

Camp 2 was still being established when we arrived, and there weren’t many tents up yet. Our group placed our tents, and enjoyed the rare clear view over nearby peaks. I felt quite good on this first foray above 6000m, although my pace from Camp 1 wasn’t particularly quick. I had a healthy appetite, and rested well through the afternoon and overnight. Many climbers planning to utilize o2 stopped at 6250m Camp 2 and descended to basecamp the next day – this would be their only acclimation rotation, and they would use oxygen from the low 6000s onwards for their summit attempt. I had heard that this was the standard tactic for oxygen-supported attempts, but was nonetheless surprised to see it employed at scale; an ascent of a 7000m peak typically requires more acclimation than this!

September 13th

6250m Camp 2 to 6650m Camp 3.

Camp 2 to Camp 3 is a very short route, quite direct and steeper than the terrain from basecamp through to Camp 2. I was able to make the ascent in just over two hours, pacing slowly and carefully so as to avoid heavy breathing and overexertion. Camp 3 is situated on a natural plateau below a gorgeous ridge of ice cliffs, well protected from the slopes above. Due to high precipitation Manaslu is notoriously avalanche prone; the upper camps below the large plateau at ~7400m have historically been hit with slides, and this season’s Camp 3 placement was intended to help mitigate that. It was a gorgeous location, with incredible views both down and up the mountain.

Our small group – three other Imagine Nepal clients, two Sherpa guides and myself – were the first climbers besides the rope fixing team to reach Camp 3 this season, and the route higher had not been opened or fixed yet. We placed our tents, and spent the afternoon looking at the route to Camp 4 above us. This would be the highpoint of my first, and only, acclimation rotation. There was no means of reasonably ascending higher, as the way to Camp 4 was bogged in deep snow. A rope fixing team of half a dozen strong Sherpa guides were to open the route and fix it in its entirety, in a few days once that snow consolidated.

I rested very well at Camp 3, with a healthy appetite and no difficulty sleeping. This elevation was a solid ~300m lower than the high camp on Pik Kommunizma, where I had spent an unpleasant night almost a month earlier. I was uncertain how much acclimation I had retained from my time on Kommunizma and in the 4330m Moskvina Basecamp, and was quite relieved to respond well to the elevation at Camp 3.

September 14th

6650m Camp 3 to 4900m Basecamp.

A big descent day. The large ice steps were all smooth enough to rappel, on account of well-fixed ropes. Descending was a slog, but relatively fast; only 4 hours from Camp 3 to basecamp. There was no rush, given an entire day budgeted for descending.

September 15th – 17th

Rest days in 4900m Basecamp.

I focused on good nutrition, lots of sleep, and calm mental focus throughout these three days. I was feeling very uncertain as to whether or not my acclimation would be sufficient for a no o2 ascent, and consulted online with several friends and partners who between them had a wealth of 8000m experience. I also received helpful perspective from Pakisani mountaineering legend Sirbaz Khan, who was climbing under Imagine Nepal’s logistics, and from Imagine Nepal’s leader Mingma G. Their combined advice and experience put me somewhat at ease; I decided that I should be well enough acclimated to make a solid attempt.

September 18th

4900m Basecamp to 6250m Camp 2.

The first day of my summit push was one of the longer ones, as I opted to skip Camp 1 and climb directly to Camp 2 from basecamp. The intention was that this first big output day would be offset by a shorter day two, ascending only from Camp 2 to Camp 3, a more reliable (shorter term) weather forecast for the proposed summit day, and a better two night rest interval in the mid ~6000m range. Slower climbers departed a day earlier, and included Camp 1 in their push. This tactic seems to be quite standard on Manaslu, as it gives guides better flexibility with their clients. One strong climber I’m aware of departed basecamp a day after I did, and climbed directly to Camp 3.

On Pik Kommunizma I had taken the opposite side of this strategy, and opted to add a day so as to make for two shorter and easier first days rather than a huge single day’s push. By my reckoning, this decision is really contingent first upon weather reliability and second upon confidence in one’s physical fitness.

September 19th

6250m Camp 2 to 6650m Camp 3.

A short, easy day ascending 400m to Camp 3. We took our time on this day, and tried to move at a low intensity pace.

September 20th

6650m Camp 3 to 7430m Camp 4.

More than the summit day, Camp 3 to Camp 4 felt like the crux of the route. We departed Camp 3 very early in the morning, making most of this ascent in the dark. Many climbers began to use oxygen on this move, and some continued to the summit in a single push on account of superb weather. My understanding is that most climbers who start on o2 from their Camp 3 departure continue to use it, at a low flow rate, overnight at Camp 4. The route from Camp 3 to Camp 4 is long and very sustained, relatively steep the entire way, and mentally feels endless due to the visual illusion of false tops throughout. Due to foreshortening of the mountain ahead, each rolling crest of the route looks like it might be the last – but isn’t!

This was a long and arduous day, and the first day that I used my down suit for an entire day. At almost 800m of elevation gain, Camp 3 to Camp 4 is comparable to summit days on many other peaks, and easily as taxing. The route is much, much steeper and more strenuous than Camp 4 to Manaslu’s summit. In total, this ascent took me an incredible 12.5 hours of output. We began very early in the day, so as to maximize rest time in Camp 4 before the summit attempt. This worked out very well for me, as due to my good acclimation I was able to both eat and sleep comfortably at 7430m Camp 4.

September 21st

7430m Camp 4 to 8163m Summit.

Awake at midnight, Pa Dawa and I began moving at approximately 1 a.m. I had trouble getting one of my crampons on, as the bulky chest and stomach of my down suit made it difficult to see my feet in the dark. Pa Dawa helped me, and I couldn’t help but think of all the anecdotes of ‘commercial climbers who can’t even put their own crampons on’! I kept my down suit hood up as we climbed up into darkness, my headlight inside illuminating only a small bubble of light on the snow in front of me. We greeted other Imagine Nepal climbers on their way out of camp 4, but with supplemental oxygen they quickly outpaced me. The down suit is a remarkable piece of equipment, highly versatile for venting and layering. I had a perfect micro-climate inside of the suit, and few issues with cold. My toes did become quite cold in the hours before sunrise, but I was able to manage by applying a focused ‘wiggle step’ technique – adding a full toe wiggle into my rest step rhythm at the conclusion of each step up.

The terrain immediately out of camp 4 was gently sloped. The majority of the route to the summit was similar, with the exception of one ~100m section of steeper terrain without fixed ropes. Most of the climbing to the summit only involved sustained rest stepping without use of a jumar, periodically switching the wire gate on my leash across fixed rope anchors. I left my ice axe in camp 4, and climbed to the final plateau below the true summit using two trekking poles. I climbed to the summit itself with only a jumar, empty handed.

A few hours into the summit push Pa Dawa, who climbed using o2 from 7430m C4, told me “You’re moving too slowly. I will run out of o2 if you continue at this pace. You must either go faster, or use o2”. This sparked a fierce intensity in me, and prompted me to push myself quite hard; I had resolved to either summit without o2 or to retreat, but not to use oxygen for ascent. I placed my full mental focus into my breathing and my rest step output, stopped only to drink or apply sunscreen, and made each stepping movement as efficient and as precise as possible. The elevation was enormously challenging for me, and I struggled with my breath and output rhythm every step of the way.

Sunrise brought a burst of energy and enormous stoke. We were already at or close to 8000m when the sun hit, and the morning light brought both warmth and a clear view of the route to the top. Other Imagine Nepal clients, new friends whom I had shared many meals with in basecamp, were descending from the summit, and we met at dawn below the final fixed ropes. They offered encouragement, and were proud to see me climbing without o2.

The final section of the route to the true summit was nowhere near as severe as I had expected it to be. A great boot track had been broken in, traversing past the false summits and then ascending steeply on fixed ropes to the true high point. While the anchors, a loose piton and some pickets, were a little bit dodgy, jumaring up to the high point was neither difficult nor particularly exposed. The view from the top was unambiguous; there was no more mountain, nor any higher pinnacle, to ascend. The weather had been flawless from camp 4, with almost no wind and clear skies, and the summit area was no exception. I was even comfortable removing my gloves. On the summit I waited a few minutes to take my turn standing at the top, chest and hands above the final snow cornice, but was very keen to begin descending immediately. Pa Dawa persuaded me to wait while he prepared two magnificent videos: one of the view from the true summit, and one of me on the top. I took several photos, but most were poorly framed – Pa Dawa’s photo and video at the summit were welcome images of the environment, of my state at the top, and of the view.

On the way down from the summit I sat down to rest at around 7600m and vomited until my stomach was knotted empty. Between C4, the summit, and my return to basecamp I consumed nothing but Coca Cola, Honey Stinger energy gels, a cup of juice generously provided by Nims Dai’s team at Camp 1, and a litre of water mixed with Cyclic Dextrin carbohydrate powder – a gift from my partner Reuben on Pik Kommunizma. Feeling far from spent after summiting, Pa Dawa and I decided to descend all the way to 4900m basecamp in one push. We knew that the food, sleep, and general environment of basecamp would be far preferable to another night at a high camp, and worth the exertion of a big descent. We ended up completing the ~3200m descent in approximately 9 hours. The descent was long and arduous, but we moved with high spirits.

In basecamp we received a warm welcome. One of the basecamp team met us at the edge of the lower glacier with Coca Cola and water, and in basecamp I enjoyed a hot tea before lying down. I had no appetite, difficulty sleeping, and fairly severe cognitive fog that evening, but knew that I’d ‘made it’ the entire way, up and down, and would easily be able to descend even further the next day.

Thoughts on Manaslu

Manaslu was not a difficult climb in any technical sense; the vast majority of the climbing route was fully fixed and broken in by local Nepali guides and porters, and the (severe if not fixed) ice steps throughout the icefall and middle mountain required only simple jumar and rappel techniques. Manaslu was not a difficult climb in any logistical sense; all tents were hauled and placed by Imagine Nepal’s team, I carried nothing besides my personal gear throughout the climb, I cooked no food and prepared no water, I did not route find, I did not dig tent platforms, and all decisions regarding timing and weather were made for me. Manaslu was not a difficult climb in regards to risk; objective hazards were almost entirely mitigated by the fixed route, I climbed with Pa Dawa at my back whenever on the mountain, and on summit day Pa Dawa had a spare bottle of oxygen in his pack – ‘psychological oxygen’ – for use in case of emergency. The Imagine Nepal basecamp was absolutely luxurious by my standards, which bolstered the quality of my rest intervals and likewise kept me well nourished physically and relaxed mentally. In many respects, Manaslu was significantly ‘easier’ than any 7000m peak I have ever attempted.

The worthy challenge of Manaslu was in its elevation. Output above ~7700m was brutally difficult for me to maintain, and I felt that there was an invisible wall after which it required extreme focus to manage my breath rhythm and pacing. I moved much slower than the majority of climbers who were making use of o2, but still set a decent time of almost exactly 6 hours from camp 4 to summit. Subjectively this felt like much longer, struggling to continue moving, to rest step as efficiently as possible, and to minimize my breaks to water consumption or sunscreen reapplication. Both physically and mentally, Manaslu was a very challenging mountain to climb.

I lost roughly 11% of my body weight throughout my Pik Kommunizma and Manaslu expeditions, despite concerted efforts at weight gain: the Turkish restaurant and lots of baklava in Dushanbe after Pik Kommunizma, loads of ice cream and lamb noodles in Kathmandu before Manslu. I was particularly weak on return to Manaslu basecamp, significantly worse off than on Kommunizma. The afternoon, evening, and morning after summiting I experienced significant cognitive fog, was uncoordinated and clumsy, and had no appetite. I developed a productive cough on return to basecamp, which almost immediately resolved when I reached Kathmandu at low elevation. I was quite thoroughly slammed by the summit and descent, and if I had been unsuccessful I likely would not have had reserves for a second attempt. I had intended to attempt a climb of Ama Dablam after Manaslu, but was so worn down that I opted to change plans and go to South East Asia for sport climbing beside the ocean instead.

I was delighted to succeed on Manaslu. Despite the climb’s ‘accessible’ nature, due entirely to the degree of infrastructure and support present on the mountain, 8000m without o2 was the real deal, a true challenge and a worthy goal. Climbing guided was expensive, but after the fact I feel that I derived significant value from the expense. Pa Dawa was an enormously supportive, experienced, and reliable partner, and was pivotal in making my climb happen smoothly. He was a talented cook, knew everyone on the mountain and was thus able to secure a three person tent for the two of us to share at every camp, accompanied me from Kathmandu throughout the approach trek and entire climb, managed to capture excellent images at the summit, and quietly ‘had my back’ throughout the difficult C3-C4 and summit days. I was lucky to climb with him, and must not only express gratitude for his support, but also emphasize the role which his presence played in my successful summit.

I would attempt another ‘low’ 8000m peak, one of the nine below ~8400m, but next time would feel comfortable doing so unguided with an independent team. I would not consider changing my attitude towards the use of o2 in the future – I would only use supplementary o2 for the purpose of an emergency descent – and now realize that this decision quite possibly precludes me from ever making an attempt on Everest, K2, Kangchenjunga, Makalu, or Lhotse.