Contents

- Pik Kommunizma / Pik Ismoil Somoni

- Basecamp and Access

- Route Description

- Trip Report and Schedule

- Images

- Thoughts on Pik Kommunizma

Pik Kommunizma / Pik Ismoil Somoni

The highest mountain of the Pamir range, the highest mountain of the former Soviet Union, the highpoint of modern day Tajikistan, the world’s 50th highest mountain, one of the five 7000m Snow Leopard peaks. 7495m Pik Kommunizma, renamed as Pik Ismoil Somoni by the Tajik state in 1998, is an absolutely enormous mountain which utterly dominates its surroundings. A primordial axe-head ridge of black rock, Kommunizma rises above the high Pamir Plateau, which is itself guarded on all sides by severe walls and high ridges of shining snow. Climbing Kommunizma by the normal route is akin to climbing three mountains; the ~6250m Borodkin Spur from ~4300m basecamp, 7007m Pik Dushanbe from the ~5850m Pamir Plateau, and finally Kommunizma itself. The normal route is long and circuitous, ‘uphill both ways’, exposed to inclement weather and to some degree of objective hazard.

I first set eyes on Pik Kommunizma in 2018 during an ascent of Pik Korzhenevskaya, a nearby 7105m mountain which shares basecamp. My timing and strategy were insufficient to make an attempt in 2018, but Kommunizma’s presence was nonetheless a constant. The distinctive summit ridge was always there, looming on the horizon, clearly visible from each of the lower peaks which I climbed on that expedition. In 2023 I found an opportunity to return for a proper attempt, and was ultimately successful in summiting.

Basecamp and Access

The vast majority of the time Pik Kommunizma is climbed from Moskvina Glades Basecamp, as the normal route and all of the mountain’s most well-known variations begin here. Moskvina is a decades-old location which has seen use, in various incarnations, since Soviet times – although I did learn during this particular visit that the original basecamp which was employed in the earliest years of the area’s climbing is located significantly lower down the valley than present day. Moskvina is a rare oasis of greenery in a high altitude desert; there is a small lake (albeit polluted with rusted oil drums, amongst other ancient detritus), enough grass grows to attract herds of mountain goats, and several streams flow in from various glaciers.

Moskvina has been dramatically upgraded and improved since my 2018 expedition to Pik Korzhenevskaya. It is now one of the better basecamps that I have had the pleasure of staying in. The ‘old Moskvina’ of 2018 was an absolute dump, rife with food insecurity, stomach issues likely stemming from bad water, poor sanitation, leaky tents, and generally miserable facilities. The ‘Moskvina of today’ offers 24/7 hot water, a free hot shower at any time of day one pleases, an indoors hand-washing station with abundant hand soap, clean cooking and eating facilities, an excellent revamped Russian sauna, water sourced from glacial runoff well above living quarters, and solid operations management facilitated by Ak-Sai – an operator of good reputation and considerable renown on the Snow Leopard peaks. The staff at Moskvina this year were competent, friendly, and accommodating throughout my one month stay – especially the kitchen staff and the head basecamp manager. The situation at Moskvina has been massively improved and modernized, and I would be very surprised if there isn’t eventually an attendant rise in climber interest with the area as a result.

The basecamp package cost me $3,300 $USD, inclusive of a shared tent, three meals per day for 30 days (I ended up staying in basecamp between 7.29 and 8.25), all permits, use of facilities, a hotel stay on either end of the trip, airport transfers, and helicopter rides both in and out. The only area for improvement which I could really pin down as significant, would be the rather limited stock of for-purchase goods such as beer and soft drinks; everything was sold out within a week of helicopter restocking. The pay-per-use satellite internet connection was somewhat dodgy, but good enough for basic usage and always fairly refunded when non-functional – certainly much better than nothing.

Moskvina is traditionally accessed by helicopter, although the lengthy approach trek is definitely possible and seems to attract interest from a few brave souls every season. In 2023 most helicopters flew from Djirgital, a small town an 8 hour drive from Dushanbe on very rough mountain roads. A few flights did run directly from Dushanbe, specifically the first flight in and the last flight out; the helicopter was provided by a Tajik airline this year, and we infer that it is parked and maintained at the Dushanbe airport. The helicoper flight takes about 40 minutes from Djirgital, and is incredibly scenic, offering magnificent views of the Pamirs and tantalizing first glimpses of Pik Korzhenevskaya and Pik Kommunizma. Helicopter flights were managed externally, but booked alongside the basecamp package; there’s no independent booking, and the helicopter is specifically offered as a part of the logistics operation for climbers.

Route Description

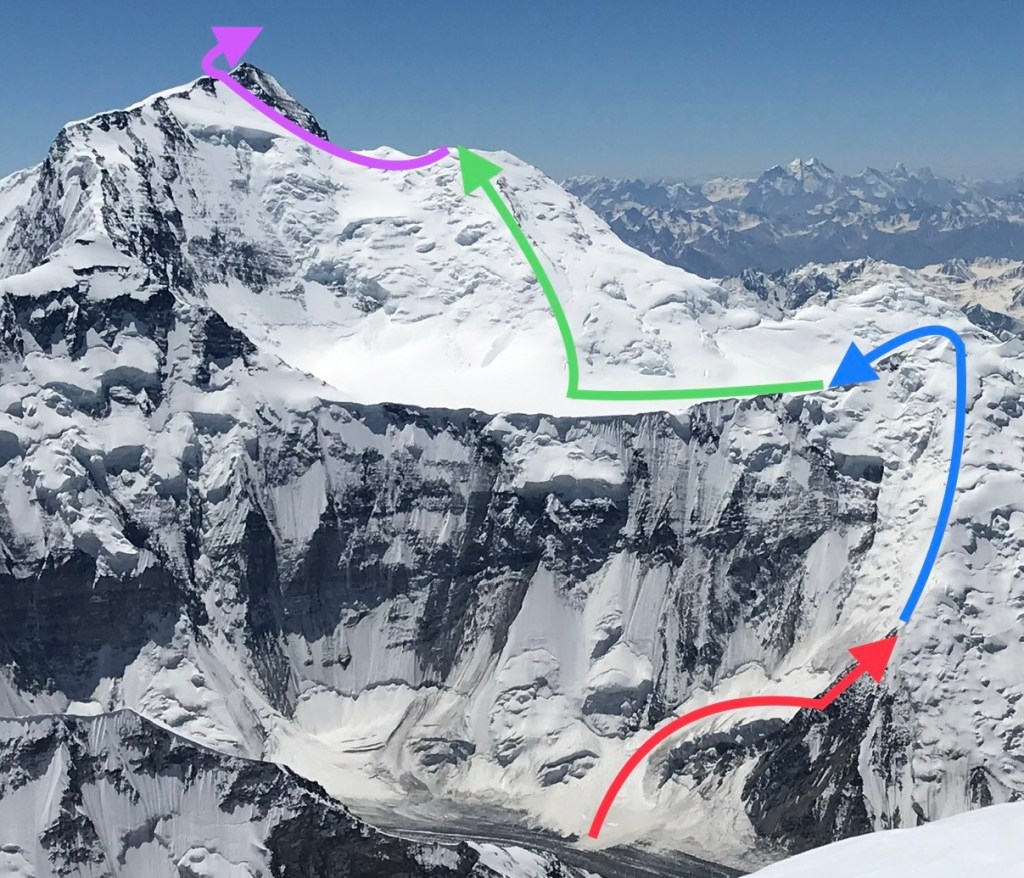

~5200m Rock Camp to ~5850m Pamir Plateau: Blue

~5850m Pamir Plateau to ~6950m Pik Dushanbe: Green

~6950m Pik Dushanbe to Summit: Purple

~4300m Moskvina Basecamp to Ramp

A moderate moraine hike with several variations through the rocks and lower glacier, with one small river crossing. Quite well cairned throughout, straightforward directly up the valley. A wide, open space below the ramp presents a good cache spot, and has a simple helicopter pad marked out with white rocks.

Ramp to ~5200m Rock Camp on the Borodkin Spur

The infamous ramp remains objectively dangerous, exposed to avalanche from serac collapse, but is definitely less risky than in years prior. Conditions were very dry throughout my time in Moskvina this season, and the ramp area was no exception. Most of the giant, hanging seracs seemed to be stable, and only one upper corner was responsible for the majority of releases. Several large slides did hit the route, but never when climbers were present. The largest slides seemed to be in evenings, perhaps due to freeze / thaw cycles. Moving briskly, exposure to the most dangerous sections of the ramp was limited to around 15 minutes on descent. The rockfall and collapsing lower glacier of Korzhenevskaya, found at around 5000m, felt significantly riskier than Kommunizma’s ramp did.

After gaining a few hundred meters up the gently sloped snow ramp, an obvious rock ridge littered with old fixed lines starts up the Borodkin Spur. The rock is pitted and scratched from many decades worth of cramponing; I took my crampons off and was able to actually enjoy the terrain. This was the most interesting part of the entire route, and there is even a cool notch / tunnel which one must climb through. Despite a fair bit of choss the rock ridge mostly offered great scrambling, with exposure and excellent views over the lower glacier. The Rock Camp is found at the top of the ridge between 5100m and 5200m, and has about a dozen good pre-built tent platforms, solid relics from expeditions past.

~5200m Rock Camp to ~5850 Pamir Plateau

The Borodkin Spur continues on snow past the Rock Camp, up to around ~6250m. Numerous small campsites can be found along the way, mostly underneath cornice formations, but nothing is particularly large and it would be difficult to place more than a few tents. During my ascent I camped the first night at ~5350m, on a level snow shoulder speckled with hairline crevasses. There are several significantly steep sections of climbing, all of which had been fixed by guided parties earlier in the season. Two cornice steps offered difficulty, even fixed, due to slight overhang and exposed ice. On descent several of the fixed ropes had melted out v-thread anchors, and on the way up one section of fixed line was no longer anchored safely. Caution with anchors placed by others, and a spare screw or two, is essential.

The Borodkin Spur is long and really drags on; cresting the top and getting a first view of the Pamir Plateau below is truly wonderful. The descent from ~6250m down to the Pamir Plateau at ~5850m is mostly quite moderate but did exhibit one significant section of steep and exposed water ice, which we fixed one of our ropes on. Ascending from the plateau some 400m back up the Borodkin Spur after summiting was arduous, and seemingly endless when fatigued.

It is worth nothing that the Moskvina side of the Borodkin was crevassed, with most frozen over or filled but nonetheless present. In the dry conditions which we enjoyed everything was nicely visible, and hazards were very easy to avoid. In deeper snow, or with no boot track, it would be well-advised to consider roping up.

~5850m Pamir Plateau to ~6950m Pik Dushanbe Camp

The Pamir Plateau is enormous and mostly flat; one can camp essentially anywhere. Crossing the plateau isn’t hard at all, and snow conditions were excellent for us. There were no significant crevasses along our line of crossing, nor any nearby it. I can envision significant difficulty if met with deep snow on the plateau, but this would also implicate the entire route, especially the Borodkin Spur.

The ascent of Pik Dushanbe is long and repetitive, a moderate snow slope the entire way. There were no particularly steep sections, and limited terrain variation. A few crevasses lurk along the line of ascent, but were mostly straightforward to see and avoid. A highly visible rocky ridge characterizes the upper half of the slope, and provides a good landmark for navigation. On descent, in whiteout, this rock band easily kept us on route and making good progress. The campsite at ~6950m is located in a nicely sheltered col near the top of Pik Dushanbe, with flat space for quite a few tents. Several much smaller tent platforms exist in the rocks along the ridgeline, with space for one or two tents every two hundred meters or so. Views of Kommunizma’s summit pyramid are grand and imposing from the 6950m camp; the rock wall hangs ominously over Pik Dushanbe and appears much larger close up than from afar.

~6950m Pik Dushanbe Camp to 7495m Summit

A short descent of some ~100m from camp leads to a rolling ridgeline towards the base of Kommunizma’s summit pyramid. There is a fair bit of ascent / descent throughout this section, more than one would expect when viewing the mountain from a distance, which becomes quite demoralizing when on the way back into camp after summiting. In particular, the final slope back up to 6950m camp is heartbreaking to climb after the summit. The ridge soon reaches the base of the summit pyramid, where a massive snow slope accesses the upper summit ridge. There was a decently switchbacked boot track on our summit day, but no ropes had been fixed by earlier teams. Sections of the face are quite steep, and there were patches of icy terrain where fixed lines or running protection would have been very welcome. A bad fall anywhere on the face would be difficult to arrest, and the subsequent runout is enormous.

On reaching the upper ridge of the summit pyramid the gradient steepens significantly, and the ridge drops off in a severe cliff. The degree of exposure is startling, as the mountain’s upper aspect provides no clue towards the summit ridge’s sharp edge when viewed from a distance. The sharp ridgeline ascends abruptly, with a slight rolling traverse as one reaches Kommunizma’s summit. A single fixed line was a welcome discovery here, protecting the steepest pitch of the exposed ridge. The summit is small, but flat and unambiguously the peak’s high point. A plaque and some broken poles marked the top, with Pik Korzhenevskaya prominently visible across the valley and the entirety of the Pamirs stretched out far below.

Trip Report and Schedule

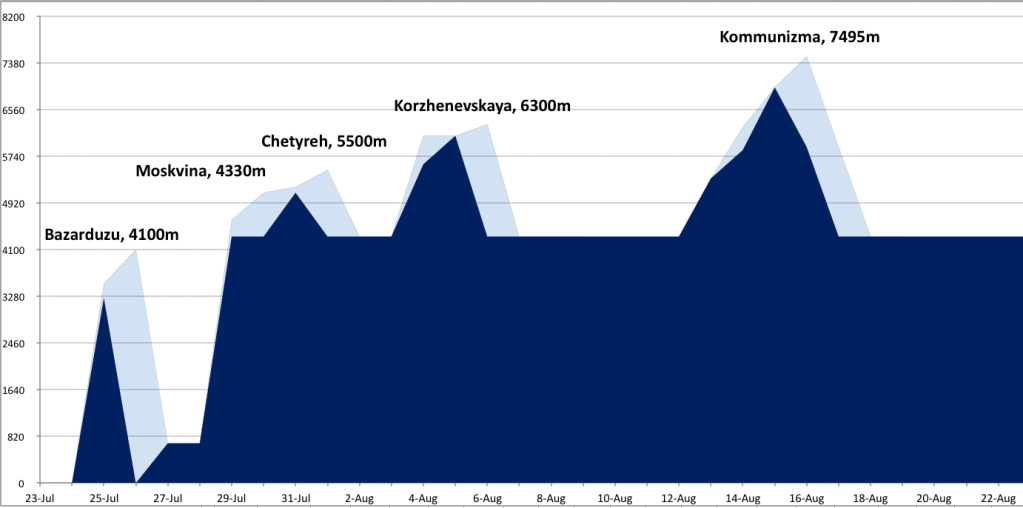

I flew into Moskvina with friends Eric and Andreas, whom I had climbed with in 2019 on Noshaq in Afghanistan. Prior to Moskvina Glades, Eric, Andreas, and I pre-acclimated by hiking Bazarduzu in Azerbaijan, where I tagged 4100m. Torrential rain on the only day scheduled for the hike soaked me to the skin, and I turned around well short of the summit. Once in Moskvina I engaged in two subsequent acclimation intervals on Pik Chetyreh, to 5500m, and on Pik Korzhenevskaya, to 6300m. Icy conditions prevented our group from attempting a Chetyreh summit, and personally feeling bad on Korzhenevskaya I opted to stop at 6300m and spend a night at 6100m instead of pushing for the summit. I previously summited both Chetyreh and Korzhenevskaya in 2018.

On this trip Eric, Andreas, and I split the cost for the services of a private meteorologist, Chris Tomer, whose forecasting proved to be remarkably accurate and useful for strategizing. With a night at 6100m and a high point of 6300m under my belt, I rested for six consecutive days in 4300m Moskvina, waiting for a forecasted weather window with low wind. This acclimation schedule proved to be more than adequate acclimation for 7495m Pik Kommunizma, likely due to a significant base acclimation period and high quality rest spent at 4300m.

Following my six day ‘Russian rest’, I started up Kommunizma alongside Paul Schweizer, an experienced friend whom I knew previously from Pik Lenin in 2016, and from Pik Korzhenevskaya in 2018. On day two I convened with Reuben Kouidri, who alongside Eric and Andreas had opted to make a single lengthy push straight from basecamp, combining what I had split into my own day one and day two schedules. Reuben and I subsequently shared a tent and stove, and climbed as partners throughout the remainder of my Kommunizma ascent. We summited together on day four from Pik Dushanbe camp, and descended to the plateau in the same day.

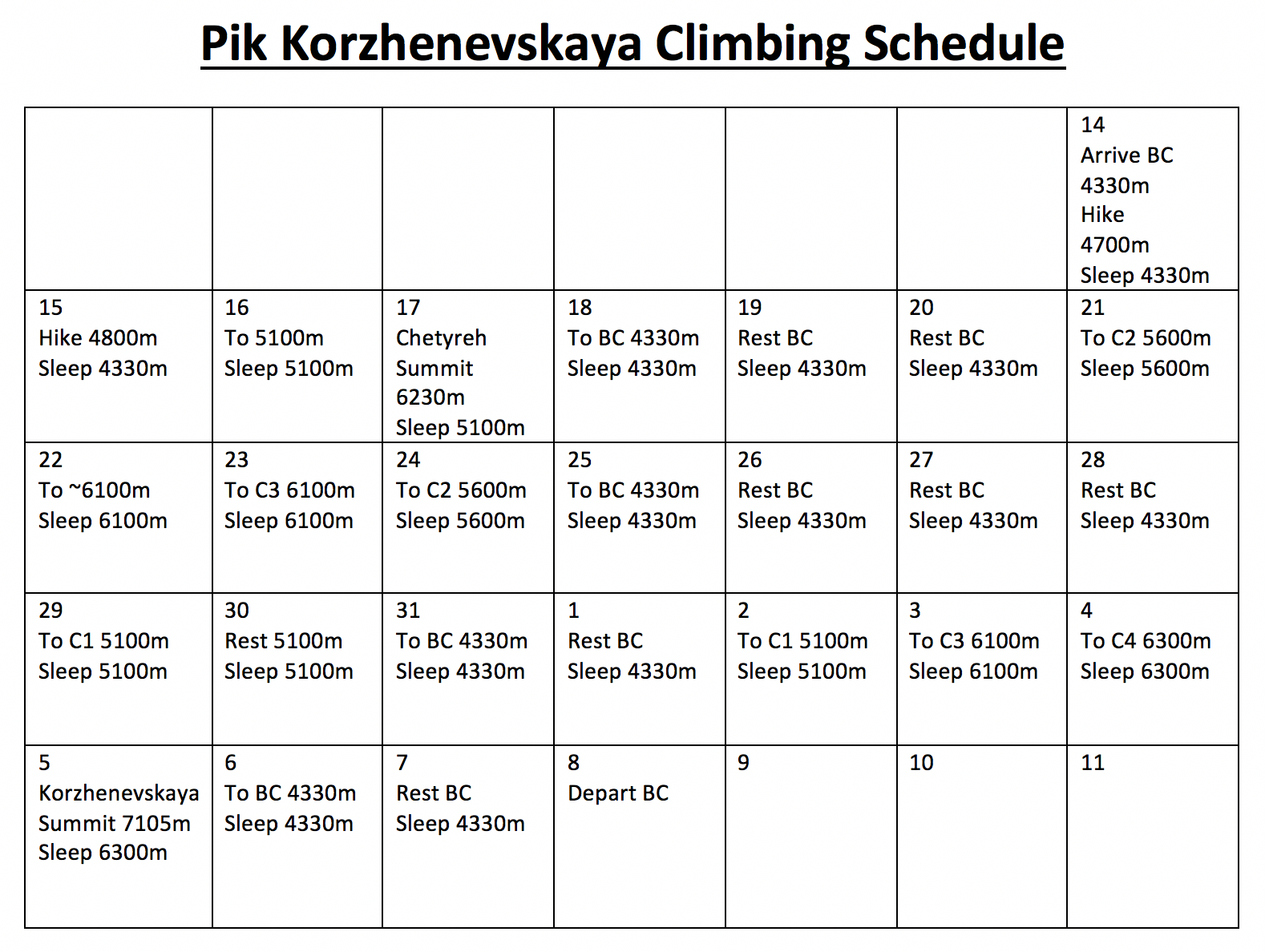

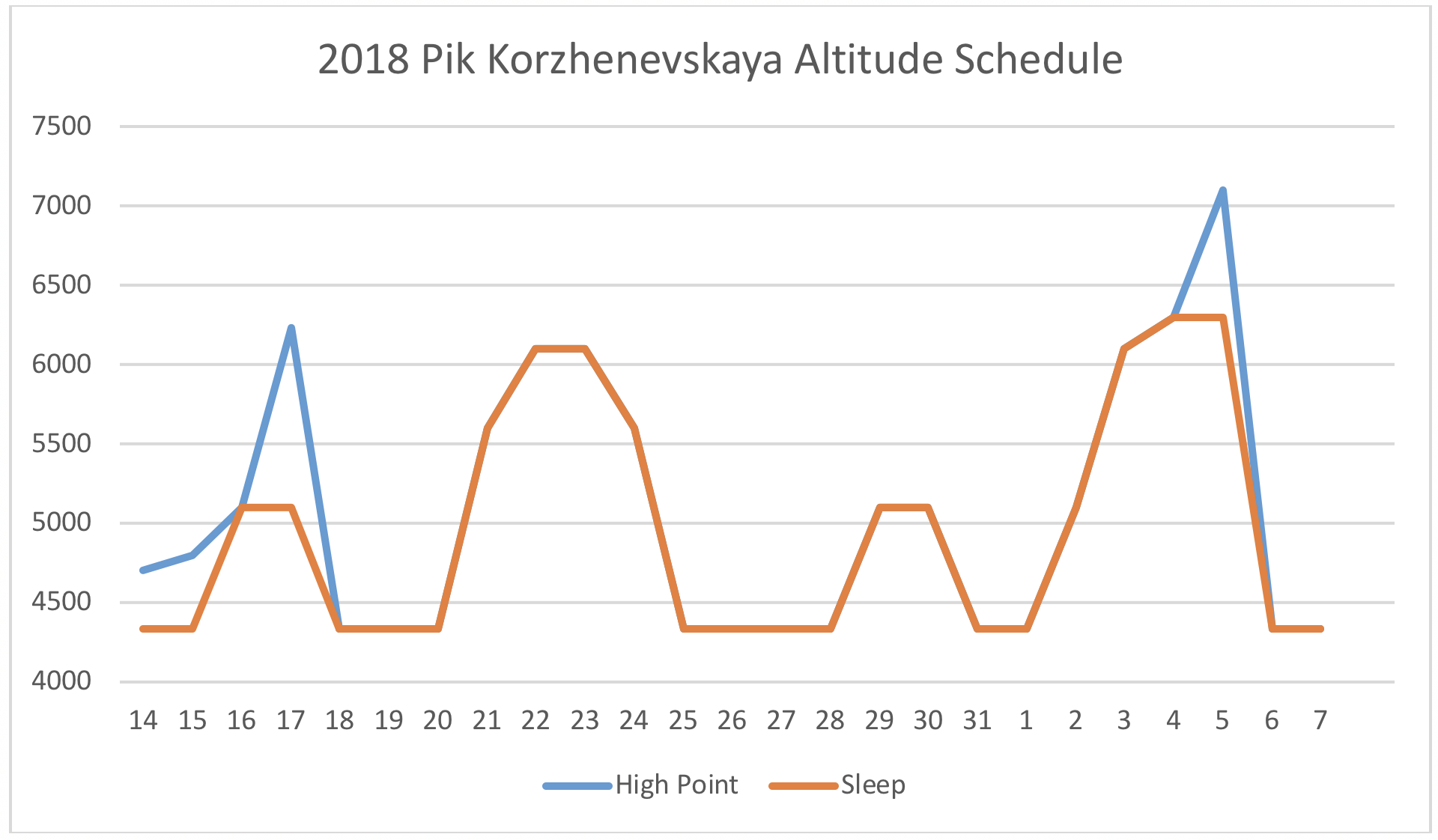

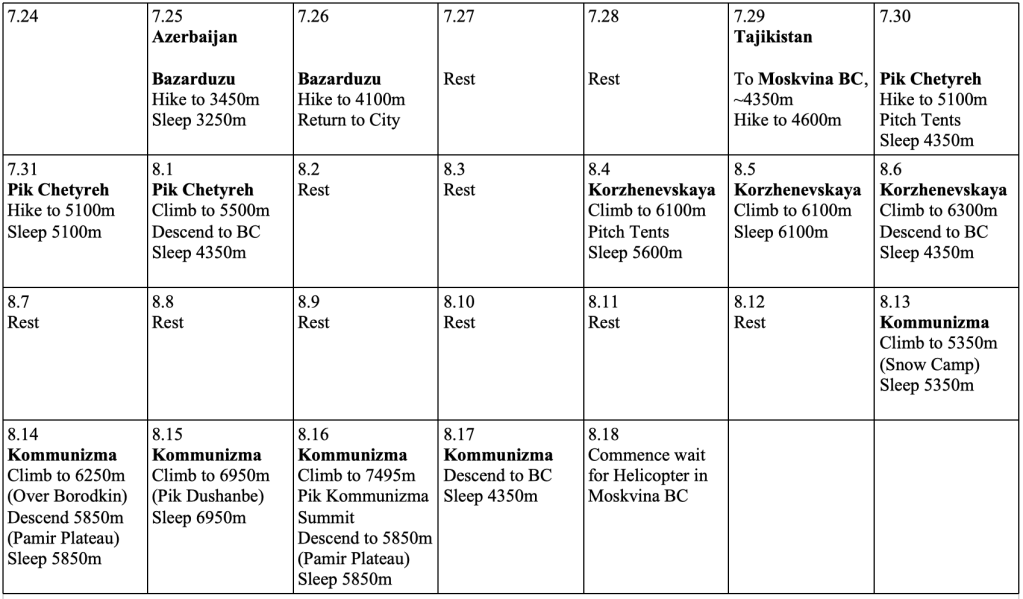

Calendar

Acclimation Graph

Day-by-Day

Day One: August 13th

~4300m Moskvina Glades to ~5350m Snow Camp

8 Hours, +1050m

Having marinated in Basecamp for about a week, our small band of five unguided climbers – Andreas from Denmark, Eric from the USA, Reuben from the UK, Paul from Scotland, and myself from China/Canada – were all feeling antsy and eager to move. I had been resting very well since coming down from 6300m on Korzhenevskaya, supplementing my Basecamp diet with high-protein food from Dushanbe, maintaining finger strength with simple hangboarding (on my small, one-handed fingerboard) every other day, and doing some light bouldering on (surprisingly decent) nearby blocks when it was warm enough. Our professional weather forecast pointed to low winds and warmer air temperatures on August 16th, and it became increasingly apparent that this would be the best summit day over the coming weeks.

Andreas, Eric, and Reuben planned to wait as late as possible for a firm weather confirmation, and then pull a long first day climbing overnight from Basecamp all the way to the 5850m Pamir Plateau. I had done poorly with the subsequent recovery at altitude following a similarly lengthy 11.5 hour day while acclimating on Korzhenevskaya, and wasn’t keen on straining myself during an ‘approach day’. The long Korzhenevskaya push served as a reminder – after almost four years away from high altitudes – making me cognizant of the ethos which had always worked very well for me on previous climbs; slow and laid back days leading up to a strong summit attempt.

As luck would have it, my fourth friend Paul was both keen to aim for our August 16th summit day and similarly aligned with my aversion to a long first day’s climb. I had initially met Paul on Pik Lenin in 2016, where we climbed together through the lower icefall and to 6000m, and had run into him again at Moskvina in 2018, when I summited Pik Korzhenevskaya. Paul is something of a ‘quiet legend’, enormously experienced and accomplished in the mountains, yet humble and very reserved in downplaying his significant achievements. Paul and I didn’t plan to meet in Moskvina this year, but were happy to run into each other once again. We had always gotten on well, shared a similar enthusiasm, and had a mutual sense of trust in safety standards and competence. Paul had also been up part of the route already, had gas cached on the mountain, and knew conditions well – extremely fortuitous for me! The two of us agreed to climb together, up 1000m from basecamp, to camp at ~5350m on a snow shoulder near the middle of the Borodkin Rib where Paul’s cache was located.

Reuben and I collaborated to pair up after the first day, sharing a tent, stove, and gas supplies. I’d carry the tent up on day one, and Reuben would climb overnight with Eric and Andreas to ‘catch up’ with me, bringing stove and gas, on day two. Reuben and Eric would each carry a radio, for check-in with base camp. Paul graciously offered to share his stove and previously cached gas on day one, saving me significant weight. Paul and I made an early start, taking advantage of the excellent (eggs, and more food than normal!) ‘early alpine breakfast’ offered by the basecamp cook. We set off at a leisurely pace along a well-marked trail, through the moraine up the valley towards Kommunizma. Paul already knew the moraine well, which saved us some trouble in avoiding repeated descents and ascents.

The approach was uneventful, and happily the glacial ramp at the base of the Borodkin was likewise very straightforward and smooth. Two small avalanches did release above us, but were so far off that they didn’t hit, nor even spray, the route of ascent. The ramp is heavily crevassed, but everything was so dry and clearly visible that we didn’t see a need to rope up. The rock ridge past the ramp offered engaging climbing, and I enjoyed the scrambling far above massive glaciers, with awesome views and big exposure on both sides.

Past the rock ridge the snow slopes of Borodkin’s Rib begin at around 5200m, and a dodgy looking fixed rope greeted us, protecting an icy initial section of climbing. Under test strain most of the rope pulled free, some 50m of line. We gingerly ascended up the first section without weighting the remaining lines, rightly nervous of any anchor’s integrity. I finally got high enough to inspect the remaining intermediate anchor, a good v-thread, and confirm that it was safe for us to jumar the line. This process of testing, ripping out, and then inspecting the ropes wasted a fair bit of our time, but it was still only early afternoon and we had a comfortable buffer. We soon found ourselves at Paul’s cache on a flat, but exposed, snow shoulder at around 5350m.

Here we dug a little bit to flatten out tent platforms and then pitched our twin single-walled tents, hairline crevasses conveniently located right at the doorways. I gratefully accepted Paul’s gracious offer to melt snow on his stove and with his cached gas, and managed to eat a huge meal of freeze dried food, cheese, mixed nuts, and snack foods. We settled in for an early rest, and I slept remarkably well throughout the entire evening. The decision to take a slow first day had worked out for me, resulting in a very minor fatigue load, a healthy degree of food consumption, and an excellent night’s sleep at a relatively low elevation.

Day Two: August 14th

~5350m Snow Camp to ~6250m Borodkin Spur

8:30 a.m. – 14:00 p.m.: 5:30 Hours, +900m

~6250m Borodkin Spur to ~5850m Pamir Plateau

14:00 p.m. – 15:00 p.m.: 1 Hour, -400m

Paul and I took our time in the morning, given the relatively short ascent which awaited us. After a good breakfast, again with Paul generously sharing his stove and gas, we packed and were moving by 8:30 a.m. About an hour later we heard voices and saw figures below us; Andreas, Eric, and Reuben had caught up, climbing since around 2 a.m. All three seemed to be in good spirits, and indeed there was plenty to be happy about: a decent boot track continued the rest of the way up the Borodkin, with only a thin dusting of snow over top of it. As we ascended, a large group of Russian climbers descended past us. They were ‘tourists’, on an epic ‘mountain tour’ traverse expedition, and had hiked into Moskvina before summiting both Korzhenevskaya and Kommunizma. Their plan had been to complete a traverse of Kommunizma, descending to some distant village on the side opposite to Moskvina. They had summited Kommunizma some days prior, but one of their members had fallen on descent and been seriously injured; they were headed back to Moskvina for an evacuation. We wished them good luck.

Making steady progress upwards, I reached the top of the Borodkin, around 6250m, at 14:00. The upper Borodkin was viciously cold due to high winds, some of the worst we experienced throughout the five day climb, and it was a relief to find shelter on the far side where the descent begins. The first views of the Pamir Plateau from the top were breathtaking; the plateau is much larger and more impressive than the mountain’s profile would suggest from a distance. The plateau not only stretches out between Borodkin’s Rib and the base of Pik Dushanbe but is also remarkably wide, and falls off starkly to the Moskvina side where it is guarded by severe walls of rock and ice. Pik Dushanbe and Kommunizma preside grandly above the plateau; cresting the Borodkin is akin to having summited a 6000m peak and discovering the lofty base of yet higher mountains behind it.

Descending 400m down the plateau-side of the Borodkin was mostly quite moderately sloped and took one hour, slowed somewhat due to a large patch of exposed water ice which we opted to fix one of our ropes on. Eric proficiently placed two screws, and a treacherous traverse with bad runout became an easy diagonal rappel. On the plateau ahead of us we met Russian guide Pavel and his client Olga, who gave us good advice on the flattest section to set camp. We got our tents up, collected excellent slabs of compact snow for cooking, and settled in for the night.

Day Three: August 15th

~5850m Pamir Plateau to ~6950m Pik Dushanbe

9:50 a.m. – 17:20 p.m.: 7:30 Hours, +1100m

Our group opted for a late start, anticipating a rapid ascent up Pik Dushanbe. We broke camp and were moving by 9:50 a.m. Eric and I opted to rope up and go first on the first section off of the plateau, as visually there seemed to be potential for hidden crevasses. After some 300m of elevation gain it became clear that snow conditions were excellently crisp, everything dry enough for good visibility of any hazards, so we unroped and continued separately.

Ascending Pik Dushanbe was a real slog. The terrain drags on and on with minimal variance in slope or character, an enormous moderate snow slope the entire way, 1100m up. Around halfway up there is a prominent rock band which serves as a clear landmark, with a few small camping platforms dotting the rocks every few hundred meters.

At 16:30 p.m. and around 6700m, Andreas, Reuben and I stopped for a short rest at one such site and briefly discussed the possibility of pitching camp below the 6950m high camp. Eric was already well ahead of us by the time we had stopped, and was out of shouting distance; we couldn’t make out if there were larger sites higher up or not. Andreas committed to high camp, while Reuben and I briefly ran through the pros and cons of stopping where we were. We quickly decided that given we had already somewhat underestimated the timing of our ascent up Pik Dushanbe, we would do poorly to similarly underestimate the summit day by starting too low.

Less than an hour later, at 17:20, Reuben and I reached the 6950m camp. It had been a long day, and a few hours slower than anticipated. In hindsight we probably could have climbed faster or started earlier in the day, but despite it being late the weather was very cooperative; almost no wind. Andreas and Eric had their tent up and were preparing for the night, so Reuben and I likewise focused on getting everything unpacked and organized. Three Russians we had met a week earlier in basecamp – Constantine, Dima, and their guide – were also in their tent, having summited that morning. They had spent several days waiting out bad winds in high camp, but gave us encouraging information on the good condition of the route.

Reuben wasn’t feeling well at all, and complained of blurry vision and stomach issues – he had significant trouble eating, and vomited up most of his food. To make matters worse, when helping him dump a bag of chocolate mousse I accidentally managed to spill most of it onto his outer boot shells!

In the tent, small tasks at this high elevation felt slow and difficult, and I was generally uncoordinated – as evidenced by the chocolate spill. Yet in spite of this I generally felt pretty decent, and was able to eat a fair amount of my cheese, sausage, and snack foods for dinner. I boiled water nonstop, right until sunset, and contentedly drank over a liter of tea, plus a big bowl of sugary hot chocolate mixed with whey protein. Paul arrived late, right at sunset, and I greeted him with a half litre of hot water. We went to sleep early, planning for a 5 a.m. start, and I slept quite well given the elevation.

Day Four: August 16th

~6950m Pik Dushanbe to 7495m Pik Kommunizma Summit

6:45 a.m. – 11:45 a.m.: 5 Hours, +545m

7495m Pik Kommunizma Summit to ~6950m Pik Dushanbe

12:00 p.m. – 14:20 p.m.: 2:20 Hours, -545m

~6950m Pik Dushanbe to ~5850m Pamir Plateau

17:45 p.m. – 19:45 p.m.: 2 Hours, -1100m

I woke up at 4 a.m. and began preparing for a 5 a.m. start to our summit attempt. In lieu of cooked food I ate a bowl of dry muesli, some energy gels, and a large hunk of Tajik cheddar cheese. The stove fired up, but the first of what would soon become many problems reared its head when it became apparent that our gas canister had frozen overnight, despite our storing it inside of the tent. With the gas flowing at a pathetic dribble, just barely hissing into the burner, melting snow was taking an inordinate amount of time. A second problem; Reuben’s only Nalgene water bottle cracked when we filled it, spilling water and rending it useless for a summit bid. The third issue; Reuben’s boot lace snapped, likely due to the mousse that I had spilled on the boots the day prior freezing solid overnight. Fourth; I managed to capsize a full litre of melted water, wasting it, after waiting over an hour to prep it. Fateful bad luck and the consequences of minor carelessness were conspiring against us.

Andreas and Eric managed to depart on time, at 5 a.m., and Paul shared some water before heading out shortly after them. While the various mistakes and setbacks which Reuben and I experienced read as trivial in writing, they posed rather significant challenges at 7000m. We moved slowly, with diminished cognitive alacrity. We swapped an empty soda bottle for the busted Nalgene, carefully tied the boot lace back together, slowly warmed our gas can, and borrowed Andreas’ stove from his tent (we had cached about 1 kg of spare gas on the plateau, and an abundant supply at Pik Dushanbe Camp) so as to run two burners simultaneously. Reuben and I, in reflection well after the fact and in a nice restaurant at sea level, both agreed that we handled these setbacks well; we cooperated, communicated, stayed as focused as we could, and eventually sorted everything out.

Nonetheless, we departed almost two hours later than intended, at 6:45 a.m. This could have been catastrophic for us, but we managed to maintain a healthy pace and make up for lost time. We descended from Pik Dushanbe quickly, following Eric, Andreas, and Paul’s boot tracks across the ridge line. This initial ridge section involved more descent than I had expected, but eventually terminated at a small rock band, the base of Kommunizma’s upper face and summit pyramid.

The upper face presented an endless slog, but happily, mostly on visible boot track. Constantine’s tracks from the morning prior were still in place, and Eric, Andreas, and Paul had further beaten them in. Time dripped and crawled during the climb up the face, my complete focus dialed into each step’s crampon and axe placement. The terrain was fairly steep, with some small sections of water ice, and a fall would have been difficult to arrest well. Ahead, I saw Andreas and Eric traverse left off of the switchbacks that Reuben, Paul, and I were ascending; a voice came over Reuben’s radio, Zaravko the basecamp manager, watching through a telescope and telling us to continue climbing directly. I passed Paul, we wished each other luck, and I continued after Reuben up the switchbacks. Andreas and Eric came into visibility on the ridge above us, moving fast towards the summit. Carefully passing a final 5m section of sketchy water ice, I eventually reached the summit ridge at the rightmost snow notch.

The exposure was incredible, with the face dropping off abruptly and a sharp ridge line extending up to the right. The Pamirs spread out below under a deep blue sky, dozens of 5000m and 6000m peaks, stark contrast between black rock and white snow. Behind us Korzhenevskaya presided with particular prominence, standing alone over the lower glaciers, its long summit ridge and route of ascent perfectly framed against the sky. Reuben was just slightly ahead of me, as the two of us began up the ridge towards the highpoint.

Andreas and Eric met us halfway up the ridge and offered encouragement, telling us that we were almost there. I congratulated them; they had both completed the five Snow Leopard peaks with their ascent of Kommunizma, and just had to descend safely. Fifteen minutes later Reuben and I were both at the summit, a small, flat, unambiguous high point marked with a plaque and some debris. We hugged, shook hands, and started quickly taking photographs. It had taken us almost exactly five hours to summit from Pik Dushanbe, a superb outcome in light of our haphazard start in the morning. The wind was sharp and biting at the top, so we quickly began to descend. We met Paul at the notch, exchanged greetings, and started down the face.

The descent required total concentration. The face is fairly steep, and sections of ice were tricky to navigate with only a trekking pole and a long axe. The ridge back to the base of Pik Dushanbe was miserable, each uphill section taxing my resolve. Pik Dushanbe itself was a hideous slog, and felt like significantly more elevation than it had on the way down. When I finally reached camp Eric and Andreas greeted me with a half litre of hot water. I told them I’d wait for Reuben, and we agreed to meet down in the plateau camp, using our satphones to coordinate if anything happened. Camp was sunny and sheltered from the wind, so as Andreas and Eric finished packing and departed I lay down in the tent to take a nap. Reuben arrived about an hour later, feeling exhausted; we agreed to sleep for one hour and then descend.

My alarm clock woke us up on time, and we began packing up. The weather shifted, and thick cloud socked us in with low visibility. Without wands marking the top of the route up Pik Dushanbe, we wouldn’t even have been able to make out the correct direction of descent. Paul arrived right as we finished packing, and told us that he intended to spend the night at Pik Dushanbe camp and descend in the morning. I asked Paul “Would you go down in this weather?”, to which he replied “No. But, you’ll make it”. Filled with renewed confidence and resolve, Reuben and I hoisted our packs and headed into the swirling mist.

The hike down took forever, the two of us fatigued and struggling somewhat through a few inches of freshly fallen snow. Between whiteout and snowfall, our old boot tracks were almost impossible to make out, but the rocky ridge served as a landmark and compass, keeping us on track along the ridge proper. After a few hours we broke below the clouds and could see the plateau laid out below us, under the glow of a glorious sunset. Andreas and Eric’s tent was clearly visible in the distance, below the Borodkin, but we both felt too worn down to cross the plateau and join them. Reuben glissaded the final few hundred meters of descent, and we pitched our little single-walled tent on the first flat stretch of snow we came across. We felt much better having descended some 1100m, and despite the whiteout hiking down had been the correct decision. We boiled water, ate some light food, and fell asleep.

Day Five: August 17th

~5850m Pamir Plateau to ~4300m Moskvina Glades

10:50 a.m. – 18:30 p.m.: 7:40 Hours, +400m / -1950m

Reuben and I slept in late, and awoke to hot sun and high wind on the plateau. We really dragged our feet, and took our time getting ready. We met Tomas and Martin, two strong Czech brothers who had skied Pik Chetyreh and Pik Korzhenevskaya in the weeks prior, as they crossed the plateau towards Pik Dushanbe. They would go on to summit Kommunizma and ski most of the descent. Reascending the plateau-side of Borodkin’s Spur was awful, our pace miserably slow. Our fixed rope was still in place on the iced-over section, and we stopped to recover my two ice screws, re-anchoring the top of the rope on a v-thread. This would later prove to be a mistake, as a day later Paul would find the rope unusable, the lower section inaccessible.

Cresting the Borodkin, our pace rapidly accelerated once on downhill terrain. We quickly found ourselves at the top of the ramp, fresh with avalanche debris, and we hustled across so as to minimize exposure. At the helipad we changed into approach shoes, an enormous relief for feet accustomed to stiff mountaineering boots. The trek back to basecamp was sloppy, our wobbly legs uncooperative on loose scree, and we both lost our footing more than once. Basecamp eventually came into view, and before we knew it we were crossing grass. Eric and Andreas greeted us, offering congratulations and sharing handshakes. After dropping my bag I immediately cracked the celebratory 1.25L bottle of Coca Cola I’d purchased ahead of time, and headed inside the kitchen hall to try and scrounge up some fresh food.

The climb was truly over, we’d made it safely back. Paul would join us in Moskvina two days later; all five of us succeeded. Eric and Andreas departed a few days later, hitching a ride on the Russian ‘tourist’ evacuation helicopter. They subsequently ascended the Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan highpoints, surveying and establishing a new Uzbek highpoint in the process, and also completing the highpoints of every one of the ‘stan countries. Reuben and I would wait 9 days for the scheduled helicopter to take us back to Djirgital, and then spend an entire day driving back to Dushanbe. The wait, while boring, served the purpose of solidifying and preserving my acclimation for subsequent mountain goals in September.

Images

Thoughts on Pik Kommunizma

Pik Kommunizma presents an enormously long route, about 3600m of altitude gain, and quite a lot of slogging up moderate glacier. After summiting, I strongly felt that I’d never climb the route again. It is too long, has far too much uphill climbing after the summit, is too repetitive, and doesn’t offer much in the way of interesting terrain. Views throughout the route were exceptionally good, especially when contextualized by prior climbs of Korzhenevskaya and Chetyreh. After Kommunizma, I felt a strong desire to climb something ‘more interesting’ (a direct route!) next time. Moskvina now offers enormous value for independent climbers, presenting great access to two 7000m mountains at a very reasonable price. The two independent Czech brothers summited Chetyreh, Korzhenevskaya, and Kommunizma in a single season. Eric, Andreas, and Reuben all managed both Korzhenevskaya and Kommunizma. The basecamp is remarkably comfortable, helicopters actually ran on time this year, and the mountains are very beautiful.

Pik Kommunizma was my first significant mountaineering goal since Covid ‘ended’ in China, reopening the border for two-way travel. I had been away from altitude, and serious mountaineering, for well over three years. Throughout Covid-related travel restrictions in China I had intensely shifted my focus and goal-setting into rock climbing, while trying to maintain basic cardio fitness through lesser mountain goals, hiking, and a little bit of cardio training. I trained quite well leading into Kommunizma, while still maintaining sport climbing activities, through a structured and committed six month endurance-oriented training regime. My good athletic performance on the mountain, and a successful summit, left me with a great sense of confidence and accomplishment; I hadn’t let go of mountaineering throughout Covid travel restrictions, and had proven to myself that I remained capable of good preparation and execution. The entire expedition was long enough for me to get back into the rhythm of my old equipment and food systems, and initial rotations up Pik Chetyreh and Pik Korzhenevskaya gave me both robust acclimation and a chance to make mistakes at lower stakes.

Good luck with conditions played a significant role in our experience on Kommunizma. Fixed ropes placed by a Russian guide two weeks prior to our ascent, and maintained by Ak-Sai, aided many of the steep sections. An incredibly dry season made for a visible glacier, and our ascent involved almost no trail breaking; the descent from Pik Dushanbe under steady snowfall was the worst of it. The climb would have been significantly harder through deep snow or up an unbroken route. The climb would have been harder, or impossible, without the camaraderie and teamwork of Reuben, Paul, Andreas, and Eric. The upgraded basecamp allowed for an excellent recovery environment, and besides a throat infection after summiting I didn’t experience any stomach issues or serious illness. Our weather forecast was invaluable, and secured a low-wind summit day for us.

We organized our climb through ClimberCA, a proxy for Ak-Sai and Tajik Peaks, although one should ostensibly be able to organize directly with either of these two companies. As of late 2023, their websites are:

Ak-Sai: https://ak-sai.com/en/

Tajik Peaks: https://www.tajikpeaks.com/en.html